17 Incredible Photographers Capturing Egypt Through a Different Lens

Irreverent, inventive, and uniquely insightful, these 17 photographers are creating their own visual vernacular to show a side of Egypt that others miss.

Words by Valentina Primo and Farah Hosny.

Photography by Ahmed Najeeb.

Walking the thin line between art, culture, and politics, there is a brimming scene of Egyptian photographers striving to redesign the outline of a land they feel misconstrued. They work in fashion; they photograph landscapes; they use their cameras to tell stories and stretch the boundaries imposed on freedom of expression in a post-revolutionary country.

From female photographers confronting gender roles in rural Egypt, to former Wahhabi members, hard-hitting photo journalists, and irreverently dark artists, Egypt’s budding photography scene takes risky roads to start unconventional business, delving into an unorthodox profession once deemed unworthy of social praise.

Hailing from Egypt’s most diverse contexts, from Mansoura to Upper Egypt to Cairo’s upscale Zamalek, these 17 photographers all strive for a common, unspoken goal: to show a side of Egypt that mainstream global narratives forget to show.

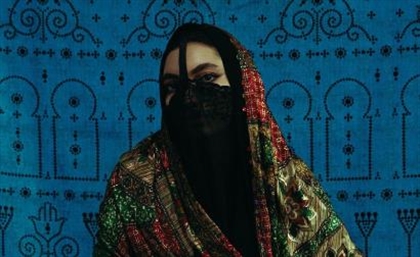

AISHA ALSHABRAWY

You could call her the badass queen of fashion photography – a self-made, iconic female warrior who broke all barriers when she decided to radically turn her life choices around, quit her corporate career, and take a ‘soul-searching’ gap year.

“I was basically trying finding out what I liked; I wasn’t worried about what I was going to do for a couple of years,” she explains. “But when you’re 20-something and you are not doing anything with your life, it is really, really hard for any parent to understand,” she adds. “Younger generations now fight for what they want. But for our generation it implied a lot of pressure because, back then, everyone was going into engineering or medicine; that’s what parents tell you. These are the ‘serious jobs',” she explains.

The first thing she did was buy a camera. And in the midst of the trips, the books, the yoga lessons, and the soul-searching journeys, her career path – a path that would see her shooting celebrities, working for Egypt’s more prominent brands, and growing a follower base of 60,000 – began to take shape. “I never really knew I was into anything artistic until really later on in life, maybe when I was 27 or 28,” explains the artist, a former Wahhabi member who had embraced the niqab. But the contrast between her former attire and her approach towards fashion is nothing but a testament to her own personal journey.

“At the time, I was fed the thought that the female body was a sin – something you should hide. But these schools of thought do not make women feel precious; they make them feel ashamed,” she confesses. “So of course a lot of what I do has a bit of a rebellion against this kind of thinking. Women should be confident in their bodies; I’m not saying they should strip naked, but I believe the female figure is one of the most beautiful things God created. That’s why women have always been muses to art.”

“At the time, I was fed the thought that the female body was a sin – something you should hide. But these schools of thought do not make women feel precious; they make them feel ashamed,” she confesses. “So of course a lot of what I do has a bit of a rebellion against this kind of thinking. Women should be confident in their bodies; I’m not saying they should strip naked, but I believe the female figure is one of the most beautiful things God created. That’s why women have always been muses to art.”

See more of her work @aishaalshabrawy.

KARIM EL HAYAWAN

Every Saturday morning, Karim El Hayawan departs from Zamalek, his camera in hand, to sneak through the nooks and crannies of Cairo’s humming neighbourhoods as they wake up to the lazy pace of a weekend noon. His Cairo Saturday Walks, originally a group’s attempt to practice, quickly became a trademark initiative gathering around 70 photographers – from the amateur to the tourist to the most influential – on periodic missions to capture Cairo’s urban soul.

“There’s no real secret to approaching people in the streets,” he says, trying to explain his knack for people-spotting. “If you are being honest and genuine about what you’re doing, they know it’s really from the heart. It’s not a cliché, it’s reality,” says the interior designer, whose immersion into photography was nothing less than an artist’s pursue to stretch the boundaries of his own realm.

Although he refuses to take credit, Hayawan’s street captures have become an icon of contemporary street photography, with a style that has amassed a follower base of over 24,000 on social media. “But Instagram is a trap. A big trap,” he quickly affirms. “Everyone is starting to take the same places and it’s starting to get a bit Orientalist,” he says. “Social media is all about what photograph you would go back to and take a look at once again. How can you do that if people are taking the same side street every time? There’s nothing interesting after a while.” At the core of Hayawan’s concern lies a fundamental premise: “Photography hasn’t changed since the 70s,” he says. “Only the machine has changed. Contemporary art, however, keeps on developing, changing vocabulary, and speaking a different language. So unless street photography catches up to the same pace, it’s going to die,” he explains. His recipe? Focusing on a concept. “The whole idea is hitting the streets, picking a concept that is genuine, that speaks the language of the day, that is contemporary, and hopefully, art.”

At the core of Hayawan’s concern lies a fundamental premise: “Photography hasn’t changed since the 70s,” he says. “Only the machine has changed. Contemporary art, however, keeps on developing, changing vocabulary, and speaking a different language. So unless street photography catches up to the same pace, it’s going to die,” he explains. His recipe? Focusing on a concept. “The whole idea is hitting the streets, picking a concept that is genuine, that speaks the language of the day, that is contemporary, and hopefully, art.”

See more of his work @karimelhayawan.

MOSTAFA EL KASHEF

“We went to art schools and we call ourselves artists but we’re scared. And we shouldn’t be scared.” Dark, subversive, and irreverent, Mostafa El Kashef and his work dance on the peripheries of what is deemed acceptable by society. “My style of photography can be weird; it comes from a dark place but this is the place I’m most comfortable in,” he says. “A lot of people might be afraid of it. But I don’t know how to do anything else.”

He is brutally honest about how he sees his craft as a way of extracting elements of yourself and laying them bare. “Photography is the only thing that lets me express what’s inside me. I’m showing you who I am as a human.” Lifeless arms lying on bedsheets soaked in blood, and stark black and white nude photography – faces always absent for the safety of the subject – are the types of images that saturate his feed. “Art conveys something that’s not always able to be expressed verbally. So you have to push everything – see what you want to do and experiment,” he argues.

The 22-year-old artist comes from a cinematic family, one that has always encouraged him to explore and experiment, but that does not mean that the nation as a whole is ready, or willing, to accept his provocative narrative. And despite the fact that his driving force is to destroy the wall that inhibits freedom of expression, he himself admits he is guilty of holding back. “Honestly, at the end of the day, yes I do have to censor myself to some extent. I couldn’t show the faces of any of the people I photographed nude because they’re afraid, of course; if someone sees their faces they’ll be imprisoned. So at the end I’m limited as well, but it’s not in my hands.”

And despite the fact that his driving force is to destroy the wall that inhibits freedom of expression, he himself admits he is guilty of holding back. “Honestly, at the end of the day, yes I do have to censor myself to some extent. I couldn’t show the faces of any of the people I photographed nude because they’re afraid, of course; if someone sees their faces they’ll be imprisoned. So at the end I’m limited as well, but it’s not in my hands.”

While he does admit to seeing an advancement in art and freedom, he laments that this is limited to the independent scene. “Don’t forget, though, that as independent artists we're also inside a small bubble of people. I’ll never reach a man living in an area 3ashwa2eya. Ill never show him anything,” he says simply. “When it comes to the actual industry, there’s people who dictate this, people at the top, and they’re not allowing the youth to break into it.” Kashef is damned in the sense that his work will never reach the masses, and they are damned in that they will never know. “People on the other side, they don’t have anything to give them a different feeling or viewpoint towards or of the world – a different idea of the world.”

He doesn’t want to fit into the woven fabric of the arts in Egypt; he wants to tear it to shreds and weave a new one, stitch by stitch. “The majority of people accept the status quo and will limit themselves like, 'ok I can't cross this line because maybe people won't like it',” he says, “But no. In my opinion, the whole thing will change if every artist pushes the boundaries of the limitations of this society and breaks it completely and goes outside it. At that time, we will create something new. We will create something real.”

See more of his work @kashef_el.

HANA PERLAS

Hana Perlas is full of stories – from dangerous experiences in Kenya, to getting close and personal with Maasai tribes, to infiltrating a fishermen community in Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. This 24-year-old girl, whose baby-like face and sweet voice hide a wild, inquisitive mind, creeps deep into Egypt’s most downtrodden alleys to capture the faces, the expressions, and the intimacy of Egypt’s ordinary life.

It was actually the January 25th revolution that led her into street photography. “I wanted to have a memory of it, but the hobby quickly transformed into my biggest passion,” she says. In a few years, the photographer managed to capture forgotten households in Egypt´s most remote places, from Dahab Island, to Nuba, to Fayoum. “At first it was scary; I’m a woman, I’m alone, and I don’t look Egyptian. But because I loved it so much, I didn’t want my fear to stop me from doing it, so I challenged myself,” she says.

Taking up a challenge is far from a new venture for the psychology graduate who defied social expectations and rejected going for the commercial road. “Everyone told me that no one would understand what I was doing,” she recalls, “but I decided to follow my passion, and eventually started getting requests from magazines who wanted photo essays. I am working to create my own field, because I’m not in photography for fame or money. I’m in it because it is what keeps me alive.” Her portraits of Egyptians, as intimate as they are heartwarming, all have a common thread, sewn by her peculiar candid outlook on the people dwelling in her homeland. “Going around the streets, you realise that a smile can go a long way. I believe that, deep down, people are very good; you just need to knock. But when it comes to Egyptians, you don’t even need to knock. I just love my people,” she says.

Her portraits of Egyptians, as intimate as they are heartwarming, all have a common thread, sewn by her peculiar candid outlook on the people dwelling in her homeland. “Going around the streets, you realise that a smile can go a long way. I believe that, deep down, people are very good; you just need to knock. But when it comes to Egyptians, you don’t even need to knock. I just love my people,” she says.

The 24-year-old artist now heads off to publish her first photography book, Ahwa Baladi, a portrayal of Egypt´s iconic old coffee shops. “They are such a big part of our culture, from the people sitting there to the details, to the pictures of Gamal Abdel Nasser next to Sisi. Those are all small details that tell you so much about Egypt.”

See more of her work @hanaperlas.

ASMAA GAAFAR

“I am a means for a message,” Asmaa Gafaar says, simply. The Daily News Egypt photojournalist has, in the past eight years, dedicated herself to being the vessel through which insights about the lives of others are disseminated, via both her profession and, by extension, an Instagram feed that captures frozen excerpts of what life in Egypt looks like, from the seemingly mundane to the moments that have impacted the nation. From protests at the press syndicate to street children playing with puppies, her unwavering aim is that her raw images “transport people to this place and return them just while they’re holding their mobile phone. They can scroll through the photos and see daily life in a different way.”

That kind of access – not only to an audience but to a photographer – is a power she attributes to Instagram and the advent of phone photography. “When I take images with my phone, I feel free,” she says of the myriad of obstacles she faces when carrying around an actual piece of equipment. The paranoia surrounding cameras in Egypt is a constant impediment to those trying to justly capture what goes on in the nation, a country where security are trained to shut down the photographing of anything they don’t think their superiors will want captured for posterity, and subjects constantly fear the ramifications of being captured in an image. “There’s a misunderstanding between me and the security forces in that you’re supposed to help me,” says the exasperated photojournalist. “I’m not doing something wrong. And the person who is afraid of being photographed is the one who feels like he’s doing something wrong.”

Though the mindset that revolves around photography in Egypt is still in flux, modern day technology and platforms allow for a new wave of expression, and breaking from the traditional and finding new avenues of expression is a concept mirrored in Gaafar’s own life. “My parents are sa3eaida,” she says, unveiling a family lineage laced with conservatism and tradition. “'We don’t have girls who work in media’ is what my father said to me when I started studying it.” Even travelling for workshops or awards was considered a problem. “It was impossible for me because we don’t spend the night outside the house, let alone travel out of the country by ourselves.”

But her father eventually relented, accepting her choice. “I think eventually he realised I wasn’t doing this to rebel against what he was asking of me; I am here to create something, and it’s something that you will respect me for later. I can tell a story through my camera. And I can create a different future for myself.”

See more of her work @asmaa_ga3frie.

TAIMOUR OTHMAN

He deflects any political conversation. He rejects being called an activist. But Taimour Othman, craftsman of the #ThisIsEgypt campaign, is the living testimony that an idea – paired with wit, persistence, and a strong will for change - can go a long way.

“I started shooting photos of places in Egypt using the hashtag #ThisIsEgypt. I wanted my foreign friends to know that it’s not always about the political aspect; that this is not a war zone and we have a clubbing, good food, and places like Sahel, Sharm El Shaikh, or Siwa,” he says.

A graphic designer by profession, Othman doesn’t consider himself a photographer, despite having crafted an idea that snowballed into a nation-wide campaign which echoed from New York’s Times Square to Italy’s national railways. “It was a reflex. If you went online in 2014 and you Googled Egypt, everything you found was negative. So I thought: I need to go around and take pictures,” he explains. “One day I had a call telling me that they wanted to use this hashtag for a national campaign. I can’t describe what I felt. Four years of hard work were finally there, and everyone was talking about it,” he recalls. Far from following artistic standards or achieving personal recognition, his initiative crafted a counter-narrative to defy the negative perception around the Middle East – and perhaps more importantly, it inspired Egypt’s people to take back the power of self-representation. “That’s why I didn’t want my name on the campaign,” he says. “I want for people to feel ownership, because if they do, they will put more effort. I wanted people to see something safe, calm, and created by us.“

“One day I had a call telling me that they wanted to use this hashtag for a national campaign. I can’t describe what I felt. Four years of hard work were finally there, and everyone was talking about it,” he recalls. Far from following artistic standards or achieving personal recognition, his initiative crafted a counter-narrative to defy the negative perception around the Middle East – and perhaps more importantly, it inspired Egypt’s people to take back the power of self-representation. “That’s why I didn’t want my name on the campaign,” he says. “I want for people to feel ownership, because if they do, they will put more effort. I wanted people to see something safe, calm, and created by us.“

See more of his work on @taimouro.

SALMA EL KASHEF

“I photographed one of my friends once – he was an actor – and then I found a publication writing that we were dating and that I shouldn’t have photographed him because he wasn’t wearing a shirt.” Art and freedom are undoubtedly intertwined, and Egypt is a country where freedom across the board is fledgling at best and art, as an element which falls under its jurisdiction, often bears the brunt of its limitations, as 22-year-old photographer and cinematographer Salma El Kashef is fully aware. “In Egypt it’s hard, because everything is criticised,” she laments.

The complications of pursuing a career in art may abound, but that hasn’t stopped the young ingénue who is constantly flirting with the boundaries of expression with the images and videos that flood her 55K strong Instagram account. “For me, art is freedom. You can't be told 'no ,don’t do this, be careful not to do that'. You have to be free and have the space, and you decide where you want to stop and where you want to place your limits.” And it is that ability to convey something through an image which drew her to photography in the first place. “Photography isn’t my official job. This is just something I love doing,” she explains. “I started photographing because whenever I see someone, I like to see them from inside; I don’t see their exterior. So I always feel like I can extract what’s inside you in a photo.” And what Kashef does in her photography, by her own admission, is draw out the darkness in people; even a cursory skim through her Instagram account reveals an aesthetic that is distinctly moody. “My photos generally have some degree of drama – I don’t usually take joyous pictures,” she admits. But the inherent drama may just be her externalisation of what she sees beneath the surface. “I don’t know why, but it’s like some sort of rule that everyone I’ve photographed has major emotional issues,” she jokes. “I’ve never photographed anyone who’s content or happy.”

And it is that ability to convey something through an image which drew her to photography in the first place. “Photography isn’t my official job. This is just something I love doing,” she explains. “I started photographing because whenever I see someone, I like to see them from inside; I don’t see their exterior. So I always feel like I can extract what’s inside you in a photo.” And what Kashef does in her photography, by her own admission, is draw out the darkness in people; even a cursory skim through her Instagram account reveals an aesthetic that is distinctly moody. “My photos generally have some degree of drama – I don’t usually take joyous pictures,” she admits. But the inherent drama may just be her externalisation of what she sees beneath the surface. “I don’t know why, but it’s like some sort of rule that everyone I’ve photographed has major emotional issues,” she jokes. “I’ve never photographed anyone who’s content or happy.”

But art in all its forms, as we all know, is not about joy; it’s about a form of expression, and Kashef wouldn’t trade it for the world. “What I do, I feel like that’s my whole life. It’s everything to me."

See more of her work @salmaelkhashef.

AHMED ZAATAR

“A piece of art is never fully completed. I don’t actually think anything is ever complete, because whenever you reach a point you always think of another goal,” says Ahmed Zaatar, with the conviction of an artist and entrepreneur who has meticulously paved his own road for a decade, with clients such as Okhtein, Fairmont, Al Ahram, and Aly & Fila under his belt.

“I sacrificed a lot for photography,” says the 29-year-old photographer, a former computer science student who gave up on his profession to take an uncertain path. “I really loved computer science, but I couldn’t see myself working in that. So I followed what I loved instead,” he recalls.

Taking on a self-learning approach and looking for mentors to help him grow, Zaatar eventually landed his first job with a major photography studio, followed by a series of positions that catapulted him to his current profession as one-man-crew who takes on everything from portraits, to interior design, to commercial shoots. “I enjoy working inside my studio, in my workplace. I need to have room to be creative; I need to have a lot of conflicting factors, and get rid of the 'don’t do',” says the artist, whose travel photos have made waves across his Instagram feed, a mixture of both art and curated commercial shots that has garnered 12,000 followers. “Sometimes you just need to get out of the work environment to get inspired and randomly shoot. I’m not a travel photographer, but it happens that I travel a lot,” he says.

“I enjoy working inside my studio, in my workplace. I need to have room to be creative; I need to have a lot of conflicting factors, and get rid of the 'don’t do',” says the artist, whose travel photos have made waves across his Instagram feed, a mixture of both art and curated commercial shots that has garnered 12,000 followers. “Sometimes you just need to get out of the work environment to get inspired and randomly shoot. I’m not a travel photographer, but it happens that I travel a lot,” he says.

However, he tosses aside the very mention of the ‘influencer’ concept: “What do I influence?” he asks, nonchalantly. “Maybe people like my pictures because they are different, but I wouldn’t know. A lot of my work is actually not on Instagram because it’s a different thing for me; I don´t think people want to see commercial work on social media,” he says. Looking to the future, the 29-year-old entrepreneur anticipates his next big venture - an incursion into cinematography - with a mischievous smile. “I’m working on it right now,” he says.

See more of his work @a_zaatar.

NOUR KAMEL

Her photo reel is a breath of fresh air; Nour Kamel sees colour where everyone sees darkness and artsy shapes where the rest would just see rowdiness. It is, perhaps, no coincidence that it all started with a few snaps of graffiti art.

“I was living in Barcelona and then Lille; I had a Blackberry with a really bad camera. But since I used to walk a lot and I was alone, I began noticing the things around me. I started taking different routes just to look around. I didn’t think it was street photography; for me it was more like, “hey mom, I’m here, and there is this nice graffiti, and really cute stickers on walls,” says the young photographer.

A member of the Cairo Saturday Walks, Kamel found in photography the perfect partner for her full-time job at Education for Employment, an NGO that trains youth on employability skills. “I think both parts blend in me. Street photography has a very grounding effect, and so does development work. Both keep me in touch with reality and allow me to express myself and give back in some way,” she says. As she speaks, Kamel graciously balances a bright green apple she pulled out of her bag from one hand to the other, an eloquent sign of her quirky, restless essence. This year, the photographer was contacted by Instagram itself, as they featured her account @nourikam amongst their flow of suggested ones. “It was really interesting to see how they viewed my pictures,” she says. “There were a lot of chairs, a lot of walls, a lot of empty places, so many colours. In the end, it is really about showing the colours that we have stopped noticing.”

As she speaks, Kamel graciously balances a bright green apple she pulled out of her bag from one hand to the other, an eloquent sign of her quirky, restless essence. This year, the photographer was contacted by Instagram itself, as they featured her account @nourikam amongst their flow of suggested ones. “It was really interesting to see how they viewed my pictures,” she says. “There were a lot of chairs, a lot of walls, a lot of empty places, so many colours. In the end, it is really about showing the colours that we have stopped noticing.”

What’s most striking about her photos is the absence of people, yet their implicit language, intrinsically human and eloquent of Egypt’s people. “When coming back to Egypt, I was amazed by how you have vivid colours in such decaying environments. Yes, Cairo is dusty, lifeless, and polluted; but it is also about incredible walls in downtown where chicken are running free,” she says. “This chaos for me is so telling of how people live. The photography I do is not taking pictures of people; but it’s really about the people.”

See more of her work @nourikam.

MUSTAFA SHARARA

A mobile photographer, influencer, and entrepreneur, Sharara is the brain behind the budding startup Excuse My Content. But long before he became an excited startup hustler, Sharara was already making waves in the digital sphere with iconic mobile shots that propelled him on to the spotlight.

The 25-year-old photographer, who started in pharmacy but was lured by the artistic field, began shooting photos with his phone, quickly garnering not only a massive follower base of 32,000, but also the attention of Instagram itself, which featured him as a suggested user, and plentiful brands who call him in for mobile photo campaigns. “It’s not about the camera but the eye,” he says.

“I don’t do portraits, I don´t do street photography, I don't do in-house or studio photography,” he says, reflecting on his style. “I take pictures of what I see through the day; I think I would define my style as random, snappy photography.” His photos, a seemingly unfiltered depiction of Egyptian life, are linked by no genre, but they tell the story of real locations unseen to a society anesthetized by economic stagnation, a fracturing social gap, and negative news cycle.

“I think people like my photos because they think that they can do this; they relate to the pictures and to what I am saying through them because they are simple,” he says. “People don´t know now that smartphones take amazing pictures.” Last year, Sharara jumped to fame when he was selected to be an ambassador of the national #ThisisEgypt campaign and travel across the country, eventually seeing one of his videos flashing in New York’s Times Square. “The first time JWT told me my picture was going to be featured in NYC, I thought they were kidding,” he laughs.

Last year, Sharara jumped to fame when he was selected to be an ambassador of the national #ThisisEgypt campaign and travel across the country, eventually seeing one of his videos flashing in New York’s Times Square. “The first time JWT told me my picture was going to be featured in NYC, I thought they were kidding,” he laughs.

But far from submerging himself into commercial photography, Sharara prefer to keeps things separate. “Photography is my hobby,” he asserts. “This is why I don’t want to work as a photographer, because I love to do it; I want to do it to change mindsets without any interference of clients or brands.”

See more of his work @mustafasharara.

JONATHAN ZIKRY

He calls himself the moment catcher. A party animal by his own admission, he is a staple at every event worth its salt in the city where every third person in the crowd knows who he is and asks him to take their photo. Jonathan Zikry is part of a new breed of photographers whose focus is on the fleeting moments that often bypass us in a blur on the nights we don’t remember the next day. “I don’t like posed photos,” he says simply, “So I was never into wedding or fashion photography. You feel like people are more themselves when I’m photographing them while they’re moving, dancing, talking to their friends. So this is more fun to me than me getting couples to stand next to each other and telling them stand this way or that way.”  But finding his way in the nightlife scene was not without its own set of obstacles. Zikry dropped out of dentistry to pursue his passion, much to the disdain of his mother - “at the beginning ommy kanit hatwalla3 feyya!” – and applied for CairoZoom, the foremost nightlife photography site in the country, in 2013. Though the photography scene has undoubtedly expanded in recent years and the concept of being a photographer is no longer looked down upon, certain restraints remain - especially in what is a relatively new sub-genre of lifestyle photography. “As a wedding photographer, you could find your way, but the nightlife scene is not easy to break into,” Zikry says. It is a role which requires fluidity and adaptation; the ability to build a rapport with those you’re capturing. “People need to know you, what you’re like; you need to know how to deal with people. You need to know how to adapt to the party mood,” Zikry elaborates. “It took me going to the same place endless times to build that trust between me and the crowd.”

But finding his way in the nightlife scene was not without its own set of obstacles. Zikry dropped out of dentistry to pursue his passion, much to the disdain of his mother - “at the beginning ommy kanit hatwalla3 feyya!” – and applied for CairoZoom, the foremost nightlife photography site in the country, in 2013. Though the photography scene has undoubtedly expanded in recent years and the concept of being a photographer is no longer looked down upon, certain restraints remain - especially in what is a relatively new sub-genre of lifestyle photography. “As a wedding photographer, you could find your way, but the nightlife scene is not easy to break into,” Zikry says. It is a role which requires fluidity and adaptation; the ability to build a rapport with those you’re capturing. “People need to know you, what you’re like; you need to know how to deal with people. You need to know how to adapt to the party mood,” Zikry elaborates. “It took me going to the same place endless times to build that trust between me and the crowd.”

But roving around Egypt’s parties for the better part of three years paid off. An indelible trust was earned. And now no one – no one – holds a candle to his ability to make someone feel comfortable in front of a camera between the hours of 12-2 AM. “People don’t ask who I am anymore. It’s just ‘this is Johnny, he shoots for CairoZoom’ and now they ask me to photograph them.”

See more of his work @johnnyzikry.

HAYA KHAIRAT

“I’m not very good at expressing myself. I’m not a great speaker and I find it hard to put things into words, so I turn to photos and video,” Haya Khairat explains. The 22-year-old photographer and cinematographer, currently studying at the High Institute of Cinema, chose the latter to pursue as her career of choice. The former arose as sort of a natural corollary, an appendage of sorts, but is also what amassed her over 50k followers on Instagram on an account drenched in dreamy photos that are soaked in emotion – whatever emotion she is incapable of expressing verbally.

But cinematography has left an indelible imprint on her and continues to seep into her other work, heavily influencing her photography style. “A picture can say a lot but motion is another thing,” she elaborates, as she strives to capture the element that is most elusive when it comes to photography: movement. “Even when I take pictures, I try to capture motion, body moves; I try and give it an aesthetic that’s like a frame out of a movie. It’s like cinematography, but still.” Despite her love of film, she freely admits to the struggles she’s faced in trying to pursue it. “Cinematography is a very sexist field in Egypt,” she says bluntly. The industry itself is male-dominated and the gender bias has deep roots to begin, with starting from the cinema institute she studies at where men outnumber women at a 10 to 1 ratio. “I think the perception established historically is that it’s a masculine profession.” The existent sexism stems in part from the intrinsic nature of the job – heavy equipment, late nights working – some of which don’t fit the stereotypical gender role and some of which are in direct conflict with Egyptian societal norms. “Loads of people told me not to study there. And when I first started it was hard for my family in the sense of like, ‘you’re going to stay out all night? You’re going to go out at 4 AM?’”

Despite her love of film, she freely admits to the struggles she’s faced in trying to pursue it. “Cinematography is a very sexist field in Egypt,” she says bluntly. The industry itself is male-dominated and the gender bias has deep roots to begin, with starting from the cinema institute she studies at where men outnumber women at a 10 to 1 ratio. “I think the perception established historically is that it’s a masculine profession.” The existent sexism stems in part from the intrinsic nature of the job – heavy equipment, late nights working – some of which don’t fit the stereotypical gender role and some of which are in direct conflict with Egyptian societal norms. “Loads of people told me not to study there. And when I first started it was hard for my family in the sense of like, ‘you’re going to stay out all night? You’re going to go out at 4 AM?’”

But Khairat persevered with a singular drive, despite the odds stacked against her. “The stress level is definitely higher for girls because you’re trying to prove yourself more than any guy, prove that you can handle it.” Her outlook remains skeptical, however; “On the one hand, institutions and the industry in the country do not facilitate women studying cinematography but, on the other, at least the collective mindset is starting to change."

See more of her work @hayawkhairat.

TIMOTHY KALDAS

Timothy Kaldas embodies the encounter of two worlds. Egyptian by essence but cosmopolitan at soul; a photojournalist by passion, and a nightlife crawler photographing events; bearer of both the global focus of a political analyst, and the intimate access to Egyptians’ private lives.

“I started by accident,” he confesses. “My friends gave me a camera for my birthday; I got obsessed about it and started shooting for clubs just to get money to buy more lenses and equipment.” When he moved to Cairo in 2009, his wedding shots were so strikingly different that they led his career on a strikingly different way. Within a few months, he was one of the city’s most in-demand photographers. His style, wedding photojournalism, takes on a photojournalistic approach to weddings, resulting in a realistic, candid portrayal of one of the most crucial cornerstones in Egyptian culture. And, for a political commentator, the job offers an unusual window to the intimacy of Egyptian life. “You get to see people’s opinions as they develop, you are constantly there seeing how they think through those issues, so this definitely has enriched my understanding of what’s going on,” he says.

His style, wedding photojournalism, takes on a photojournalistic approach to weddings, resulting in a realistic, candid portrayal of one of the most crucial cornerstones in Egyptian culture. And, for a political commentator, the job offers an unusual window to the intimacy of Egyptian life. “You get to see people’s opinions as they develop, you are constantly there seeing how they think through those issues, so this definitely has enriched my understanding of what’s going on,” he says.

Having witnessed and documented the revolution in a book titled The Road to Tahrir, the artist chose to stay away from photojournalism, following his thirst for a different lifestyle. “I documented the 18 days of the revolution, and it was inspiring as nothing ever was. But as a career path, it is not what I wanted. It’s a stressful lifestyle, you are always on call, and I prefer having a little more control over my schedule,” he says. “There is a positive dynamic in the wedding photography community. It is not aggressively competitive and everyone is growing together,” he adds.

See more of his work @timothykaldas.

OMAR MATTAR

“I wanted to show people that not everyone who takes nice photos has to have a camera,” says Omar Mattar. Something of a wildcard on this list, the 22-year-old architecture and engineering student does not have a legion of followers or a professional camera, and yet, with purely an iPhone, he has managed to beautifully capture elements of Egypt on a feed that is all perfectly subdued hues and quirky compositions.

“The photo needs to look nice regardless of what the actual contents of the photo look like,” he says, a notion highly evident in his images that will often feature dilapidated buildings or heavily rusted space frames; he often chooses spaces that are almost ugly and yet he will present them in the most hauntingly captivating way possible. And it has been this generation’s doing away with those locked, traditional, and now seemingly ancient ideals of photography that allowed Mattar to do that. “I think recently more and more people have gotten into photography – perhaps not in the traditional sense, but just taking to the streets with their phones,” he elaborates. Which is precisely what he did. “So for a lot of my work at university the professors would have us go down to study a certain area – so I would have to take photos with my phone,” he explains, “So that eventually wove into photography.” And as his one passion led to the other, he views architecture and photography as inextricably bound. “I see that the two are one,” he says, “Because, when you look at architecture, you look into the details of the building. It’s the exact same situation with a camera – you try and see things deep in the photo. If you want to create a building, you want to focus on the details to create something beautiful and it’s the same with photography."

“So for a lot of my work at university the professors would have us go down to study a certain area – so I would have to take photos with my phone,” he explains, “So that eventually wove into photography.” And as his one passion led to the other, he views architecture and photography as inextricably bound. “I see that the two are one,” he says, “Because, when you look at architecture, you look into the details of the building. It’s the exact same situation with a camera – you try and see things deep in the photo. If you want to create a building, you want to focus on the details to create something beautiful and it’s the same with photography."

See more of his work @omaarmattar.

LOBNA DERBALA

In 1948, Fathy Derbala went to Italy to study film. He could never pursue it as a career because, for an upstanding man in Egyptian society, that career trajectory was simply not considered an option. Over 60 years later, his granddaughter, Lobna Derbala, became one of the most sought after photographers in Egypt.

That radical shift within Egyptian society about how photographers are perceived speaks volumes as to the changing mentality within the nation. “In his time, it was impossible that he pursue something like that as a career,” explains Derbala, who has shot everyone from onscreen starlet Jamilah Awad for CairoScene to directing great Mohamed Khan. Decades later, the profession has gone from rejected to revered in society, and Egyptian families no longer frown upon it as an automatic rule. “My family was very supportive and they were the ones who pushed me to follow photography - and I was the one who was a bit afraid,” Derbala illuminates.

The 32-year-old professional photographer actually got her start because of her parents. “I’d grown up watching my father constantly taking family photos – pretty professional ones – and I was about nine years old when I asked for a camera, and he got me one. Back then it was the film cameras,” she recounts, “And I remember how I would get a light bulb and sit under my desk, hold it at different angles to test out the lighting. And then I would print the film and learn what I’d done wrong.”

With the advent of digital photography, which came about when she was in her first year of university, experimenting became infinitely easier until she finally honed her craft – self-taught, barring one course - and eventually entered the field and started to form a name for herself, with a heavy focus on portraiture and a certain obsession with light that has carried over from her childhood. “I’m crazy about lighting; the sun, the direction of light, where it’s going, how to capture it. Like I would be on my honeymoon and I would see over there there’s something that’s bouncing light off something else so I would run across the street because I wanted to take that photo,” she laughs. “I’m always chasing the light.”

See more of her work @lobnaderbalastudio.

AHMED HAYMAN

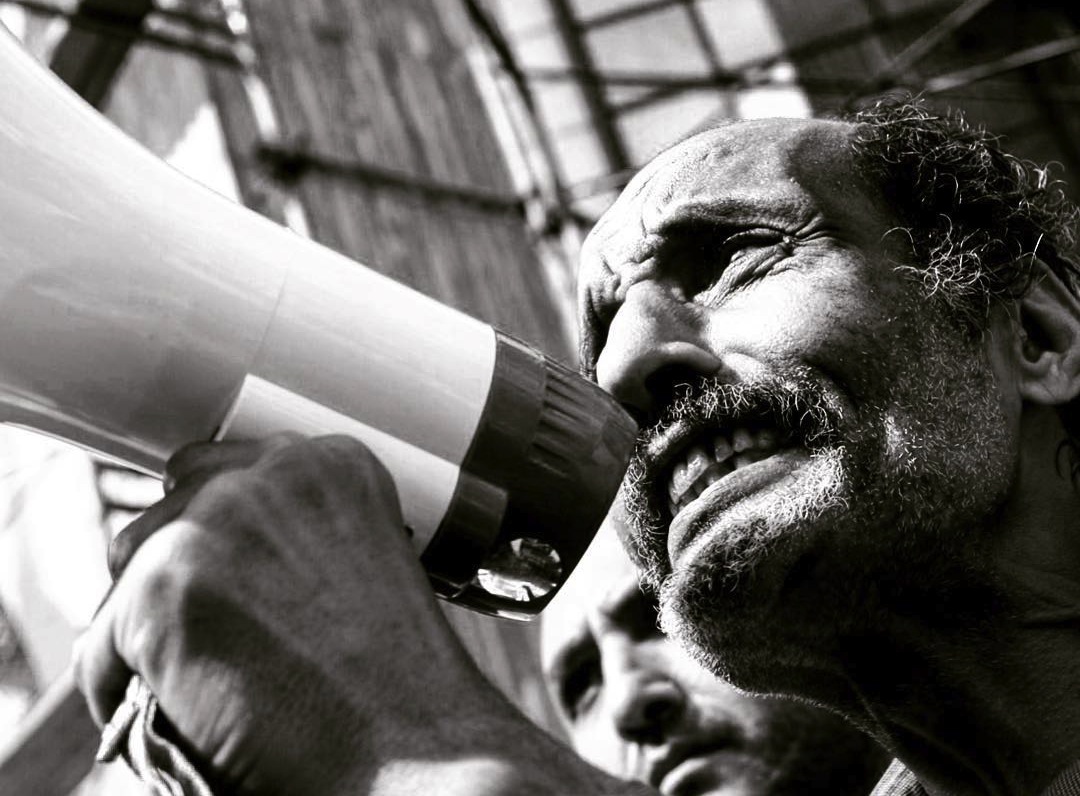

“How do you break the barrier between you and the person in front of you so that you can photograph them?" Ahmed Hayman asks. “There’s something I live by; I zoom in with my legs, not with my lens.”

The renowned photojournalist’s images tell human stories, the daily tales of ordinary people’s lives, and instantly create an invisible connection between the audience and the subject. “People feel my photos have a human element to them because I get physically close to the person,” he says simply. Hayman – who has worked for myriad media publications from Al Masry El Youm to Le Monde, has taught workshops and won awards around the world, and has just opened up his own photography hub, Beit El Soora – believes, and perhaps partially attributes his success to the fact that, connection is the most crucial element to capturing a worthy image. “It’s the idea that if I want to photograph a person in the street, I have to give him his due. He’s not someone I photograph and run off - he’s not a product.” But in creating a bond, Hayman is unique; he transcends the typical relationship between photographer and subject – he returns to each of them to give them a physical copy of their picture. “The most basic thing is to give people their photo. It’s something very personal and you’ve given him something he will never forget. People won’t remember my name – but they’ll remember the moment I took that photo. They’ll remember who I am.” His touching ritual has not only earned him remembrance across streets and alleys scattered in countries flung across the earth, but people he regards as friends around the world. “One man I photographed in Morocco, he calls me once a month just to check up on me. He’s been doing this for three years.”

But in creating a bond, Hayman is unique; he transcends the typical relationship between photographer and subject – he returns to each of them to give them a physical copy of their picture. “The most basic thing is to give people their photo. It’s something very personal and you’ve given him something he will never forget. People won’t remember my name – but they’ll remember the moment I took that photo. They’ll remember who I am.” His touching ritual has not only earned him remembrance across streets and alleys scattered in countries flung across the earth, but people he regards as friends around the world. “One man I photographed in Morocco, he calls me once a month just to check up on me. He’s been doing this for three years.”

But Hayman also believes barriers are broken by invitation, not force, and his previous role as a hard-hitting photojournalist often caused him to invoke the latter. “Courts were some of the most horrible things I’ve photographed in my life because no one wants to be photographed; neither the defendant or his parents, nor the plaintiff or his parents, or the judge…” Hayman says. “No one wants you there.” Driven by a need to capture the photos regardless because, at the end of the day, your job depends on it, “you are forced to photograph the emotions of the different people; there’s a clash and you’re caught in the middle and, emotionally, you’re destroyed.” But Hayman has long since realised his incapability to intrude on people’s emotions. “Thank God I’ve stopped doing this, and I will never do it again. I don’t like crossing people’s boundaries.”

Now he believes his role, his responsibility, is in telling the story of the aftermath – what happens after the news – as a way of creating criss-crossed bridges that connect humanity. “People have an issue with understanding each other and listening to each other and acknowledging our differences. So I go down and tell the stories of people’s lives. To see the differences in people so we can accept each other.”

See more of his work @haymanics.

AHMED NAJEEB

“I dropped out of college, left my hometown of Mansoura, and moved to Cairo to pursue photography,” says Ahmed Najeeb. The 25-year-old photographer, who focuses heavily on portraiture and has shot for National Geographic and CairoScene, was living in the small rural Egyptian governorate and studying engineering when he realised that getting a degree from his chosen major would not translate to him doing what he loved for the rest of his life. So he ditched it.

“Myself and a group of photographers in Mansoura kept trying to change the perceptions of photography there,” he says, but eventually it became evident that the industry was stuck on wedding photography and showed no signs of embracing different fields. “I thought to myself: so why am I staying here?” Defying cultural norms and parental expectations, he started carving a new path for himself. “Of course I didn’t tell my parents I’d dropped out. For about half a term, I was working and saving money and trying to set myself up because I knew that, when I told them, I needed to be prepared for that cut-off.” Unsurprisingly, when he revealed his secret to his traditional family, they balked. “They wanted an engineer or a doctor. To them, my pursuing photography was like ‘how are we going to marry you off? Are we going to tell them that our son takes pictures?’” he laughs.  But as he slowly started to cement himself in the photography scene and his family began to see that he actually had a burgeoning career – he was nabbing clients, winning awards, his photos were featured in magazines, and National Geographic came knocking – they began to accept his choice. “At first when I dropped out, I regretted it a little bit,” Najeeb admits, “Because I wanted to feel like my parents were really proud of me. But I was like no, I will focus on what I’m doing and I will make them proud.”

But as he slowly started to cement himself in the photography scene and his family began to see that he actually had a burgeoning career – he was nabbing clients, winning awards, his photos were featured in magazines, and National Geographic came knocking – they began to accept his choice. “At first when I dropped out, I regretted it a little bit,” Najeeb admits, “Because I wanted to feel like my parents were really proud of me. But I was like no, I will focus on what I’m doing and I will make them proud.”

Now his parents take an active interest in his new profession. “My mom and dad stalk my Facebook page where I display my work,” he laughs. “And, to me, the more they feel convinced, the more it encourages me to keep going.”

See more of his work @najpictures.

***

Photography by @MO4Network's #MO4Productions.