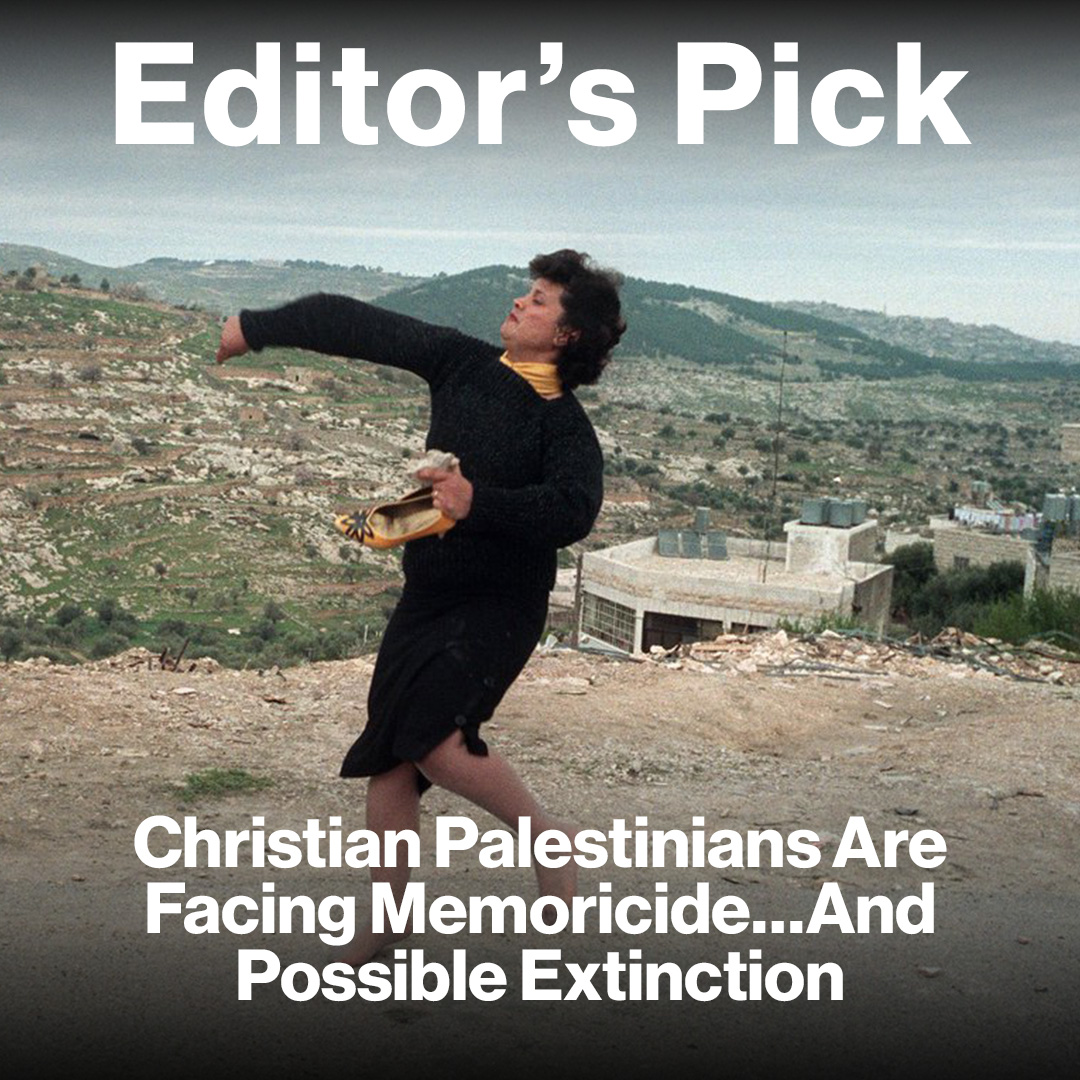

Documentary Photographer Rehab Eldalil's Decade-Long Journey in Sinai

Rehab Eldalil tells us all about her decade-long award-winning project, ‘A Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken’.

Egyptian photographer Rehab Eldalil began her search for identity in 2013, when she sat down to speak with a tribe leader in South Sinai. There, the leader told her that her last name, ‘Eldalil’, meant ‘the guide’ in his language. Through this revelation, Rehab Eldalil had her eyes opened to a rich family history of displacement from the lands of Sinai and Palestine, and she became determined to find her way back through her lens.

Over the next ten years, Eldalil dedicated herself to creating a collaborative archive with her newfound community, one that she had yearned to connect with as the 'stranger' in her project, ‘A Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken’. Eldalil invited members of the Jebelyea tribe in South Sinai to participate, whether through storytelling, poetry, embroidery or crafts. The project culminated in the creation of a multisensory book and an exhibition that is currently running at The American University in Cairo’s The Photographic Gallery until October 12th. Eldalil holds a Bachelor's and Master's degree in photography, with the latter specialising in ethics and representation. This academic background guided her in her long-term project, informing her approach to amplify the voices of communities rather than telling their stories herself.

Eldalil holds a Bachelor's and Master's degree in photography, with the latter specialising in ethics and representation. This academic background guided her in her long-term project, informing her approach to amplify the voices of communities rather than telling their stories herself.

Eldalil’s project earned her the FotoEvidence W Award in 2022 for a book publication, as well as the World Press Photo Regional Award in 2022. Her photographs have been exhibited in over 90 countries. In this CairoScene interview, we caught up with the documentary photographer during her project’s first exhibition in Egypt…

How did you first get into photography?

It started as a mere hobby back in middle and high school, but my passion for photography deepened during my university years. While there, I ventured into professional photography, though I didn't initially focus on documentary photography.

It wasn't until around 2011, right before I graduated, that I shifted my focus towards documentary photography and visual storytelling. My career took a turn towards collaborations and interactive storytelling rather than the traditional documentary approach. This transition coincided with my pursuit of a Master's degree in photography, specialising in representation and ethics in photography. I learned how to involve the communities I worked with in the creative process, making it a more collaborative and interactive experience. How does this collaboration usually manifest itself?

How does this collaboration usually manifest itself?

All my projects use a lot of multimedia, including materials contributed by the communities I collaborate with. I actively invite them to participate in the process, making the work more than just my voice as a photographer. It becomes a conversation involving all the communities I've worked with. Specifically, I applied all my approaches and methodologies in my long-term project, ‘The Longing of the Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken’. It's where I extensively explored my practice and developed my visual language within the field of documentary photography.

Can you tell us more about your connection to the Bedouin community in Sinai?

I've known them for many years, they’re essentially like family to me. And while I personally belong to the Bedouin diaspora, I'm a fourth or fifth-generation member, I wasn't raised within the community, but I was instilled with a deep respect for it as an indigenous and native group in Sinai. It's worth noting that my father is a war veteran who participated in the conflict to reclaim Sinai from occupation. So even before starting the project, I already had a strong connection and relationship with the community, thanks in part to my father's teachings about the significance of the land and the people who call it home.

However, it did feel unusual to merely photograph them because I knew them intimately, and they were not just subjects to me. This raised important questions about representation and ethics. How could I speak on behalf of a community that could express themselves so well? These questions began to surface in 2013, leading to extensive research and eventually my Master's program, which I applied to this project. What I've done with the community is invite them to actively participate in the visual dialogue. The exhibition and book feature different mediums, whether embroidery or poetry, how were these choices made?

The exhibition and book feature different mediums, whether embroidery or poetry, how were these choices made?

It was through my conversations with community members. I asked them what media they feel comfortable using and expressing themselves through. For example, because Bedouin women were historically misrepresented, many are sceptical about photography due to how they were historically portrayed as weak voiceless women, although in reality they're actually the main breadwinners. So we decided that I would print their photographs on fabric, and then they would add their own embroidery to the images. It's a traditional medium. They're really comfortable with it, and it's a way for us to converse, uh, in visuals.

Interestingly what ended up happening was that they would highlight their features, not hide them, which goes back to them feeling that they have power over their images and essentially their narrative. Similarly, because Bedouin men traditionally write poetry, we incorporated that into the exhibit and book.

That must’ve felt liberating, but also challenging, getting to experiment while working across different mediums.

Absolutely. You don't need to limit yourself in any way. Everything is boundless. The core idea of collaborating with the community was to tell such a significant story. Initially, this project served as a means for me to reconnect with my Bedouin ancestry. However, it soon evolved to encompass the broader concept of belonging, the indigenous experience in general, and the notions of home and the interconnectedness of people and the land that shape this sense of belonging. The project became very open-ended, because addressing such a delicate and complex topic solely through photography and my own perspective felt insufficient. Inviting the community to actively participate in the project was truly liberating.

It can be intimidating because you can get overwhelmed by the sheer volume of responses and visuals. However, the responsibility still falls squarely on you as the photographer and the primary author of the work. You want to ensure that the community isn't reduced to stereotypes and that their visuals or the project aren't perceived in a romanticised or exotic manner, and ensure that you respect and honour their stories.

How did the project evolve over those ten years?

As photographers from our region, and even in Egypt, we get subconsciously influenced by previous photographers. The amazing photographers from our past are mostly white men from Western countries. They looked at and photographed our regions in a very linear, orientalist, colonialist manner. So in my early photographs of the community, I felt they lacked depth. They focused on specific aspects that failed to humanise the community, and deep down, I never felt that these photos were quite right.

I knew this community had more to offer than the clichéd images of camel rides or traditional attire. I felt the need to delve deeper, conducting research to articulate my feelings. This realisation prompted me to break free from these subconscious influences. One of those ‘aha’ moments was that I knew I couldn't tell the story alone. I'm not Bedouin, and despite my close involvement with the community over the years, I was still an outsider. I needed to respect and embrace that fact, which led to the project's title, ‘The Stranger’. Since the exhibition was held abroad, including in Amsterdam and Paris, has the reception been different than in Egypt?

Since the exhibition was held abroad, including in Amsterdam and Paris, has the reception been different than in Egypt?

My primary goal with this project is to address our region, particularly Egypt. It was crucial for me to launch the book here, which I did during Cairo Photo Week last February, and I invited members of the Bedouin community to participate in the launch.

People here found it more relatable, but I had to address lingering stereotypes through discussions. The connection with embroidery, a familiar craft in urban Egyptian cities, facilitated a faster bond with the project. While the Western audience appreciated the visuals more, the project found a deeper resonance within our local and regional context. The stereotypes I've encountered here in Cairo are the same as those in Paris and Amsterdam. It's the typical stereotypes, but younger generations have managed to break through them.

How did your relationship with the community change over those 10 years?

I used to search for archives to validate my family's Bedouin roots, to ensure that my connection was legitimate. Now, however, I've now come to peace with not finding these archives because I believe I've played my part in creating new archives for the current Bedouin community. I've realised that I don't have to be a full-blooded Bedouin to work on this project, as I'm not the sole voice behind it, and it's made me more at ease with my identity and being part of the Bedouin diaspora.

- Previous Article Embrace a Vibrant Beach Lifestyle at Kai Sokhna

- Next Article A Walk Through Downtown Cairo’s Timeless Architecture