Ghassan Kanafani: Portrait of a Palestinian Revolutionary Writer

Renowned Palestinian revolutionary and writer Ghassan Kanafani’s exuberant life as a journal editor, novelist and spokesman of his country’s cause was cut short by his assassination at the age of 36.

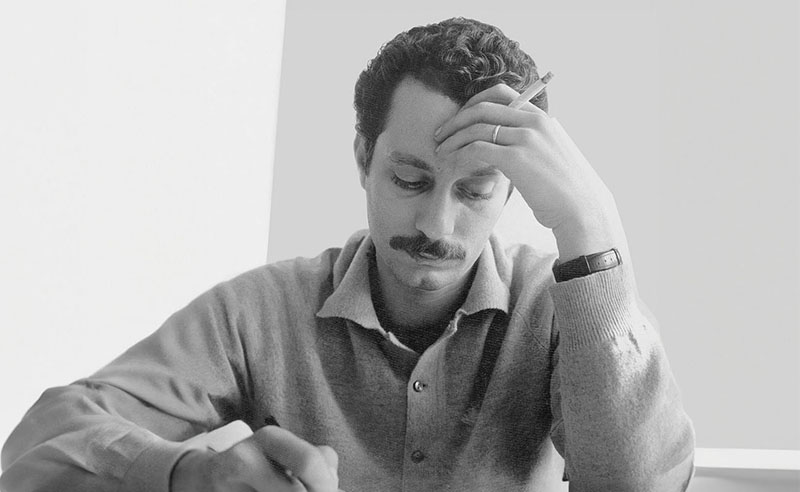

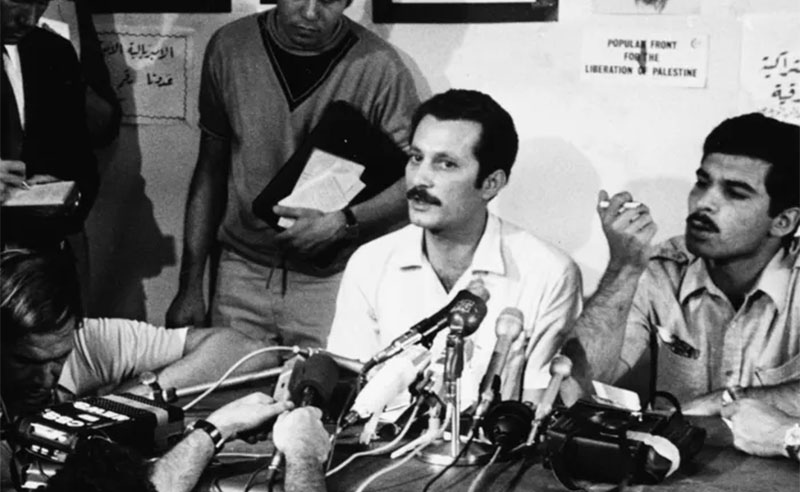

In front of a wall bearing posters of Karl Marx, Che Guevara and Vladimir Lenin and a map showing the geography of Occupied Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, sits a dashing man with striking jet black hair, vivid, vigilant eyes and a prominent moustache. In fluent English, with a lilting Palestinian accent, his side profile is calm as he answers the questions of a journalist asking him to defend the positions taken by his organisation, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and of the Palestinian resistance at large. Confidently and defiantly, he stares his interviewer in the eye.

“For us to have our dignity, respect, mere human rights, is something as essential as life itself,” proclaims Ghassan Kanafani in this 1970 interview conducted in the PFLP’s Beirut office- an interview which would bring Kanafani to fame in the English-speaking world as an eloquent spokesman of the Palestinian cause, and draw admiration from the peoples of the colonised world who at the time were waging freedom struggles of their own against their own oppressors.

“For us to have our dignity, respect, mere human rights, is something as essential as life itself,” proclaims Ghassan Kanafani in this 1970 interview conducted in the PFLP’s Beirut office- an interview which would bring Kanafani to fame in the English-speaking world as an eloquent spokesman of the Palestinian cause, and draw admiration from the peoples of the colonised world who at the time were waging freedom struggles of their own against their own oppressors.

In 1970, at the time the interview was conducted, Angolans were waging a fierce war of independence from Portuguese colonists, the Americans were committing mass atrocities in South-East Asia in the name of defending freedom, Nelson Mandela was behind bars for calling for racial equality in South Africa, and it had been only eight years since the French colonists had been banished from Algeria after a decade long brutal war with the indigenous Algerians. It was a world divided into Three Worlds, where race, creed and colour still heavily induced a sense of social subjugation amongst indigenous peoples the world over. And there he sat for all the world to see, a brown-skinned, outspoken, upright man speaking rebelliously in a tongue not his own, to a white, Australian journalist about the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination in their native lands.

Kanafani, who before this English-language interview had already been one of the most prominent Palestinian voices in the Arabic press and literary establishment, would be assassinated by the Mossad only two years later, in a car bomb placed in his Austin 1100 outside his home in the upmarket Hazmieh suburb of Beirut on July 8th, 1972. He was 36 years old at his assassination. Never wielding a gun, Kanafani’s assassination by his enemies proved strikingly the power of the Palestinian pen in their liberation struggle.

Kanafani, who before this English-language interview had already been one of the most prominent Palestinian voices in the Arabic press and literary establishment, would be assassinated by the Mossad only two years later, in a car bomb placed in his Austin 1100 outside his home in the upmarket Hazmieh suburb of Beirut on July 8th, 1972. He was 36 years old at his assassination. Never wielding a gun, Kanafani’s assassination by his enemies proved strikingly the power of the Palestinian pen in their liberation struggle.

The assassination of the “commando who never fired a gun, whose weapon was the ball-point pen,” formed part of a brutal assault by the Israeli state on the diasporic Palestinian cultural establishment, which they increasingly viewed as a threat to their plans of eradicating the Palestinian national project. This onslaught saw the assassinations of Wael Zwaiter, the renowned pacifist intellectual and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation’s head diplomat to Rome, in 1972, Basil Al-Kubaissi, Professor of International Law at the American University of Beirut, in 1973, and celebrated poet, Kamal Nasser in 1973, amongst others.

Over five decades have passed since the death of this imminent Palestinian intellectual, yet he remains as popular as ever amongst generations of Arab youth who came afterwards, his quotes filling social media and his face as recognisable to youngsters as a symbol of Arab leftism and progressivism as that of Che Guevara’s amongst Latin American youth.

Over five decades have passed since the death of this imminent Palestinian intellectual, yet he remains as popular as ever amongst generations of Arab youth who came afterwards, his quotes filling social media and his face as recognisable to youngsters as a symbol of Arab leftism and progressivism as that of Che Guevara’s amongst Latin American youth.

Born in the Palestinian city of Akka in 1936, Kanafani and his family were dispossessed of their land and home in Palestine after the 1948 Nakba. Growing up in the Syrian capital Damascus, he would read towards a degree in Arabic literature at the University of Damascus. There, he first came in touch with the man who would become a deep mentor and comrade to him, the future founder of the PFLP, George Habash. A strong supporter of Arab nationalism as well as Marxist-Leninist thought, Kanafani was expelled from the University of Damascus for his views, after which he spent a sojourn in Kuwait. It was in Beirut though where Kanafani would establish his literary and journalistic pedigree.

Establishing himself as a gifted writer in a number of Lebanese journals, Kanafani became a prolific member of the Lebanese and greater Arabic press, and later after its establishment in 1969, the legendary editor of the PFLP’s journal, Al Hadaf. In its heyday, Al Hadaf claimed a daily circulation of 23,000 copies, and was widely read all over the Arab world as well as abroad. A collection of political articles, literary articles, satire and comedy and cartoons, as well as monumental artworks in the form of posters, Al Hadaf was less of a mouthpiece for the Marxist-Leninist ideology of the PFLP as it was a trendy and romantic expression of the first-generation of Palestinian emigres scattered in capitals from London to Beirut to Cairo.

Establishing himself as a gifted writer in a number of Lebanese journals, Kanafani became a prolific member of the Lebanese and greater Arabic press, and later after its establishment in 1969, the legendary editor of the PFLP’s journal, Al Hadaf. In its heyday, Al Hadaf claimed a daily circulation of 23,000 copies, and was widely read all over the Arab world as well as abroad. A collection of political articles, literary articles, satire and comedy and cartoons, as well as monumental artworks in the form of posters, Al Hadaf was less of a mouthpiece for the Marxist-Leninist ideology of the PFLP as it was a trendy and romantic expression of the first-generation of Palestinian emigres scattered in capitals from London to Beirut to Cairo.

The project was immensely curated, created and produced at the helm of Kanafani. “He made Arab Marxist revolutionary ideas cool and trendy, unlike the boring media of the Lebanese Communist Party. He combined art with literature and information, all for the purpose of the liberation of Palestine,” wrote As’ad AbuKhalil in his essay entitled ‘The second life of Ghassan Kanafani’ published in The Electronic Intifada. Along with serving as the editor of the PFLP’s journal Al Hadaf, Kanafani was also one of the organisation’s official spokespeople to the international press, as well as a co-founder of the organisation’s information office along with poet Kamal Nasser and writer Majed Abu Sharrar (both would subsequently also be assassinated by the Mossad within a decade of the slaying of Kanafani).

The barflies of Beirut were as acquainted with Kanafani as were the working class Palestinian refugees, the glitterati and high society who formed a central part of the city’s cultural scene, and the myriad Arab intellectuals, artists and romantics who made Beirut’s pre-civil war cafe culture the stuff of modern Arab mythology. A heavy drinker and smoker, Kanafani himself was a perpetual character in the city’s nightlife scene. It was in this setting of a decadent, hedonistic and cosmopolitan Beirut that he befriended contemporary Arab literary legends such as Elias Khoury and Mahmoud Darwish. As a man, Kanafani was as vast, as scarred and as multifaceted as his revolutionary politics and contemplative fiction. “His own life was a constant struggle - with writing, with Palestine, with love, with smoking, with drinking, and, eventually, with death,” wrote his close friend and renowned Lebanese writer Elias Khoury in his essay entitled ‘Remembering Ghassan Kanafani, or How a Nation Was Born of Storytelling’. “It was his love of life that fashioned the writer, the lover, and the fearless fighter.”

Beneath the daring eyes and fiery, bold exterior of this spokesman of a vanguard revolutionary party, lay a tender romantic and a fierce lover. This side of Kanafani was exposed in a collection of letters published in 1992 by his lover, Syrian journalist and writer Ghada El Samman. In a letter to her, he writes “...Your love demands that one lives for it alone: an island that the exiled cannot reach in the waves of the vast ocean. And yet, I have also come to know your love so well that I can disappear into it.” In her own right a celebrated author, and an outspoken literary figure on Arab femininity and sexuality in the last century, the two were a pairing of immense proportions. In a letter written to her from Cairo in 1966, he suggests eschewing work-related meetings and instead be with her, “I’ll be in Beirut the 6th of December, according to the latest change…unless I flee from the conference and fly to you.”

Beneath the daring eyes and fiery, bold exterior of this spokesman of a vanguard revolutionary party, lay a tender romantic and a fierce lover. This side of Kanafani was exposed in a collection of letters published in 1992 by his lover, Syrian journalist and writer Ghada El Samman. In a letter to her, he writes “...Your love demands that one lives for it alone: an island that the exiled cannot reach in the waves of the vast ocean. And yet, I have also come to know your love so well that I can disappear into it.” In her own right a celebrated author, and an outspoken literary figure on Arab femininity and sexuality in the last century, the two were a pairing of immense proportions. In a letter written to her from Cairo in 1966, he suggests eschewing work-related meetings and instead be with her, “I’ll be in Beirut the 6th of December, according to the latest change…unless I flee from the conference and fly to you.”

His oeuvre includes several works of fiction, grappling with the notion of being from a land to which he could not return, and being part of a diaspora rich in its own right, but which now had to find cultural homes in capitals far from Jerusalem and Jaffa. Amongst his most well-known novels are the 1962 novel ‘Men in the Sun’, a reflection on life in Palestinian refugee camps, and the 1970 novel ‘Return to Haifa’, a story of a Palestinian family’s reckoning with the loss of identity and belonging brought about by the Nakba. Palestine remained the writer’s locus in his fiction as it was in his non-fiction. Questioned once about his obsession with writing about Palestine, he responded, “Do you know why most writers love Paris? Because they never lived a day in Haifa.”

Kanafani has remained in the contemporary memory, ever the 36-year-old dashing, slick and youthful revolutionary firebrand-cum-romantic-writer. His works today reflect the emotions of a generation living the first two decades of an exile and occupation which is now nearing its eighth decade. He, along with his contemporaries, an eclectic mix of impassioned artists, poets, novelists, journalists and academics born of the olive groves and zaatar fields of what Kanafani called ‘The Sad Land of Oranges’, are as important today as they were then. As the brutal occupation continues its bloodshed and dehumanisation of the Palestinian reality, it becomes evermore acute to remember this ancient nation of storytellers, centering their voice and their humanity, in a world which seeks to quieten them ever further.

Kanafani has remained in the contemporary memory, ever the 36-year-old dashing, slick and youthful revolutionary firebrand-cum-romantic-writer. His works today reflect the emotions of a generation living the first two decades of an exile and occupation which is now nearing its eighth decade. He, along with his contemporaries, an eclectic mix of impassioned artists, poets, novelists, journalists and academics born of the olive groves and zaatar fields of what Kanafani called ‘The Sad Land of Oranges’, are as important today as they were then. As the brutal occupation continues its bloodshed and dehumanisation of the Palestinian reality, it becomes evermore acute to remember this ancient nation of storytellers, centering their voice and their humanity, in a world which seeks to quieten them ever further.

Shortly after Kanafani’s death, renowned Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish penned his elegy, writing, “They blew you up, as they blow up a front, a base, a mountain, a capital, and they fought you, as they fight an army… Because you are a symbol, a Wounded Civilization.”

- Previous Article Essam Sasa Tops Spotify's Charts as Most Listened to Artist in MENA

- Next Article A Walk Through Downtown Cairo’s Timeless Architecture