Hello Hologram! The Evolution of Arabic Calligraphy

Senior Editor Eihab Boraie gets so inspired by the story of an Arabic Calligraphy Museum opening up that he set out on a journey of discovery, and an adventure of leading a team of artists to create the 1st ever Arabic Zoomorphic Calligraphy Hologram.

The origin of Arabic calligraphy is shrouded in mystery often sparking debates among historians. Despite the controversy, there are few who will deny its powerful and mesmerizing beauty. This ancient artistic art form has survived and evolved over a thousand years, and as of late seems to be making a comeback with today’s artistic youth. With advancements in technology, there is a now a wide array of techniques bringing new life to this ancient art form. Upon hearing the news, a couples of weeks ago, that Egypt has opened its first Arabic calligraphy museum in Alexandria, we decided to attempt to map its history and look into its future. Inadvertently while researching for this piece, we found the inspiration to get creative and began experimenting with technology. To our surprise, our attempts to experiment with calligraphy may have ended up possibly creating the first Arabic zoomorphic calligraphy hologram in existence.

#Egypt’s First Museum of Arabic #Calligraphy has opened in #Alexandria (Moharram Bey area) http://t.co/rlozc87B0o pic.twitter.com/3P4FT7KbEu

— Amro Ali (@_amroali) August 23, 2015

It all began with a tweet about Egypt's first calligraphy museum, but before we explain how that led to the creation of our hologram, we must first attempt to examine the origin of calligraphy. The word calligraphy is derived from the Greek words Kallos (beauty) and graphos (writing). The words were merged to describe the harmonious proportion of both letters in a word, as well as the arrangement of words on a page. Although the Greeks may have coined the term, its contested origin is likely rooted in China, Japan, or the Arab world. Considering that their styles and alphabets are unique from one another, we will focus solely on the evolution of Arabic calligraphy.

The Arabic alphabet predates the Qu’ran, and despite its existence, few knew how to read or write it. Arguably one of the most influential illiterate figures in history was none other than Islam’s messenger Prophet Muhammed. Always delivering Allah’s message orally, it was decided after his death that the Qu’ran would need to be compiled and published in order for its message to live on. The creation of the Qu’ran inspired many to learn how to read and write, and led many artists to attempt to match its beauty with creative new scripts.

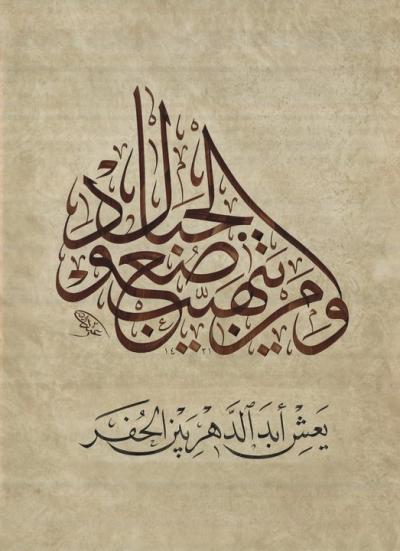

Kufic example by Mounir AlShaarani

The first calligraphic script to become popularised was known as kufic. It is believed to have emerged around the 7th century around the area of Kufa, Iraq. Defined by its angular letters, horizontal format, and thick extended strokes this style flourished, leaping off the pages of the Qu’ran and adorning architecture as well as a wide array of works of art. With time, this style would branch out to the point where artists began creatively intertwining letters with flowers (aka Floriated Kufic) or woven into knots. The branches are endless as there were no set rules. This resulted in a script that differed from region to region, and in the 12th century a shift was made to Naskh, a well defined cursive script that measured proportions of all letters to in proprtion to the height of the Alif.

Example of Naskh Retrieved from: http://www.arabiccalligraphy.com/#!/home

It is believed that Ibn Muqla (886-940AD) was responsible for setting the Naskh stylistic guidelines. The new structured style began quickly replacing Kufic as the preferred style for everything from the Qu’ran to private correspondence. Just like Kufic, Naskh would evolve creating variations known as Thuluth, Riq’ah, Muhaqqaq. The most beautiful and hardest to execute, even for the most accomplished calligraphers, was known as Muhaqqaq. Appearing in the 14th century during the Mamluk era, this form of Naskh focused on beautifying short phrases like 'B'ism Allah'.

It was from the 14th century onwards that regions began developing their own versions of Arabic Calligraphy. The Persians developed Nasta’liq, The Ottoman Turks created Diwani, and the Chinese developed Sini. Each had their own unique characteristics and variations.

Example of Diwani Retrieved from: http://www.arabiccalligraphy.com/#!/home

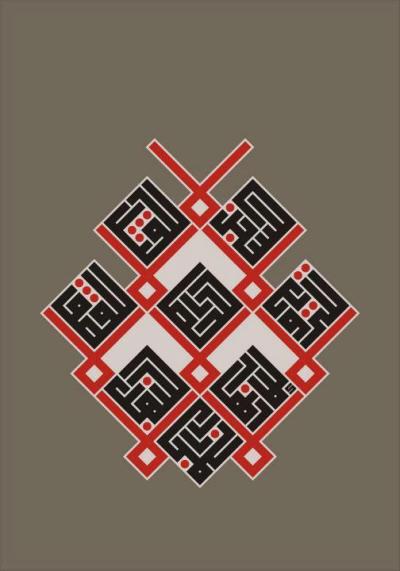

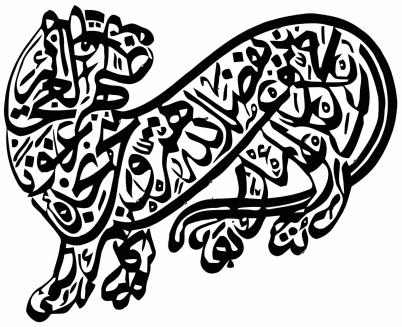

Trying to keep track of all the different variations began to seem futile, as was identifying all fonts in existence. It seemed that every generation of artists pushed themselves to find new and imaginative places to take Arabic calligraphy, going so far as making words brilliantly appear like animals (Zoomorphic Calligraphy) and even modern day objects. There was no shortage of imagination on paper. However in the 21st century there are plenty of new advanced artistic mediums that lend themselves perfectly to Arabic Calligraphy that are yet to be developed.

Example of Zoomorphic Calligraphy

Example of Modern Calligraphy Retrieved from: http://www.arabiccalligraphy.com/#!/home

Moving from paper to the streets, calligraphy began emerging as a form of graffiti known as tagging. A tag is essentially an artist’s personalized signature painted on a wall, often turning barren spaces into colourful statements. Although it is a leap from paper to a structure, it still remains to be a static variation of calligraphy. I refused to believe that with all the advancements in technology and equipment, that you can't find an example of calligraphy re-envisioned beyond a canvas. That is when I stumbled upon light calligraphy, an extremely difficult form of calligraphy that mixes long exposure photography while manipulating a light source resulting in a photo that looks like calligraphy is floating in air. It’s hard to prove who the first artist was that created this new form of calligraphy, however often cited as innovating the way are light calligraphers Julien Breton from France as well as Tunisia’s Karim Jabbari. Both these artists have made light calligraphy their signature style, and have started inspiring Egyptians to follow suit.

Retrieved from Julien Breton Facebook

Heeding the call in Oum el Donia is the dynamic duo of Khadiga El-Gawas and Amira Elsammak known as Wamda Team. Khadiga El-Gawas is an award winning calligrapher, and capturing her light masterpieces behind the lens is Amira Elsammak. Together their work has brought light calligraphy to Egyptian streets and has garnered attention and praise from both, inside and out of Egypt.

Light Calligraphy on Bibliotheca Alexandrina Retrieved from Khadiga El-Gawas Facebook

Inspired by their work, I decided to talk to our artistic team at CairoScene to see if we could write CairoScene using light calligraphy. Taking on the project was our very own photographer Ahmed Abdelmageed. The task was easier said than done, as writing CairoScene in Arabic using a flash light in thin air was tough to envision let alone create. It took several tries, however each attempt got us closer to creating a legible piece of light calligraphy.

By Ahmed Abdelmageed

Our best effort was legible but far from being as impressive as the works of previously mentioned light calligraphers. The lesson learnt is that finding the right lighting equipment can make the biggest difference and that no matter how impossible it seems, to never give up. The best results are those that are the outcome of a lot of trial and error. I knew with time and the right equipment we could have perfected the CairoScene light calligraphy, but despite it’s mind blowing qualities it remains a static image, and I became obsessed with finding a new medium to present dynamic Calligraphy.

After much research the only way I could find to bring life to Calligraphy was to find a way to create a DIY (Do-it-yourself) hologram. Proving once again to be all knowing, the internet provided me with a simple tutorial that would allow anyone to make a hologram using a plastic CD case, a smart phone, and glue. Following the guide we created a plastic prism of sorts which when placed on a phone would magically reflect the video within the prism. Needless to say we were blown away when we are able to duplicate the same hologram as the tutorial video. With a new medium to play with, I decided to see what holograms using this method exist. I was only able to find one example of an English calligraphy video. Feeling we were on the forefront of what will surely be a new wave of art, I decided to pick my favourite form of Arabic calligraphy, Zoomorphic, and enlisted the help of artist Sally Fakhr, videographer Adham Yasin, and video editor Ahmed Ashraf to create the first Zoomorphic Arabic Calligraphy hologram online. After a few attempts, Sally managed to creatively write out CairoScene in Arabic and make it look like a bird in flight. After weeks of attempts we finally had a hologram to call our own.

I couldn’t help but think that the possibilities of transforming Calligraphy into something new and exciting are endless. If this is what we can achieve in a matter of weeks, then there is no limit to what a skillful devoted artist can create in the near future. Hopefully the same creativity that spurred the past to invent creative variations of Calligraphic styles, will again emerge but with a focus on using the latest technology. With any luck the new calligraphy museum will realize that Calligraphy’s past is great, but its future looks gloriously awesome and deserves to be showcased if they want to inspire the next generation of mind blowing calligraphers.

Special thanks to:

Sally Fakhr : Designer / Art Director

Ahmed Ashraf : Visual Effects / Video Editor

Adham Yasin : Videographer

Ahmed Abdelmageed : Photographer

To learn how to make your own hologram at home click on this tutorial.

- Previous Article Span Marketing; Your One Stop Hub for Interior Design

- Next Article 10 Strictly Egyptian Moustaches That Will Inspire You This Movember