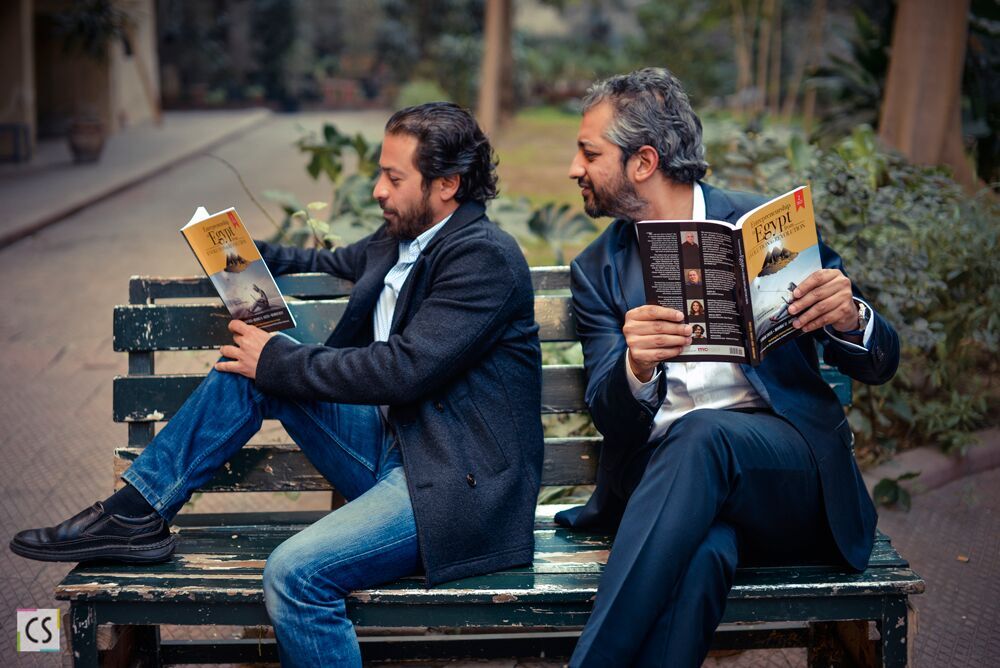

Startology: Mapping Egypt’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

From incubators to seed investors, the entrepreneurship scene boasts a science and history of its own. In an interview with Valentina Primo, the authors of Entrepreneurship in Egypt: from Evolution to Revolution deciphers the terms, the industries, and the profiles of Egypt's startup world.

Egypt’s entrepreneurship ecosystem is like a living human being, as Tarek Ali, CEO of the GrEEK Campus, puts it. Setting off to write this human being’s biography, Ayman Saeed, Mahmoud Wasfy, and Mahinaz El-Aasser embarked on a journey exploring the intersection where Mohamed Ali Pasha, the Arab Spring, the theory of change, and the entrepreneurial generation meet. The result, Entrepreneurship in Egypt: from Evolution to Revolution, is a radiography of the Egypt’s startup ecosystem that not only blends the stories of innovators with the voice of investors and prominent mentors, but also acts as a guidebook for would-be entrepreneurs to understand the phenomenon that is radically transforming the Middle Eastern economy. In an interview with CairoScene, Saeed and Wasfy, who have also founded Startology, share some insights on the startup world, from the impact of the shared economy to the profile of the entrepreneur persona.

What is Startology and how did it come about?

Wasfy: Our aim is to create a vertical accelerator programme that works differently than the traditional model. We want to involve corporations working in a specific field and connect them to startups whose product or service benefits these sectors. We want to bridge the gap between the expertise and access to market from the corporate while supporting entrepreneurs; similar to what Techstars is doing in the US. We are closing our first deal with the first corporate client, in the real estate field, very soon.

Saeed: We started working in the entrepreneurship arena after the revolution, four years ago. Our turning point was the Cairo Startup Cup in May 2013, where we were chosen by USAID to run the Egypt Competitors’ Programme. That was our first contact with real entrepreneurs.

People outside the entrepreneurial scene often do not understand the difference between a startup incubator and an accelerator. Can you illustrate it?

Saeed: Yes, there is a whole science behind it, and entrepreneurs know it very well, that’s why they use this lexicon. The main difference is seed funding. An incubator will host the teams and provide entrepreneurs with mentorship and services. An accelerator, aside from physical space, mentoring, and services, will also provide seed funding. Funding starts with pre-seed money, usually between 50,000 and 100,000 LE; angel investors usually come in later with seed funds for around 1 million LE. The next stage would be serious A investment. But, the main objective of an incubator is to develop an idea into a prototype in order to do market research and showcase it to customers.

"It is happening organically [...] It is starting inside universities; [...] and most [students] are using their graduation projects as an initiation for their own company," says Ayman Saeed.

How do you see this evolving? Are smaller companies breaking a highly monopolised economy and getting a share of the market?

Saeed: I think it is happening organically and in parallel, so there is no direction or coordination from the state in fostering it. We believe it is starting inside universities; students are aware and most of them are using their graduation projects as an initiation for their own company. Then, they have the ecosystem that can help them in the idea stage. This is why they are starting to evolve. Before the revolution there were lots of entrepreneurs, such as ITWorx, but there was no ecosystem gathering these people and fostering them. They were shaping the path on their own. Now it is different: if I get an idea, I know where to go and how much funding I can get.

When we compare the ecosystem with those abroad, the persona is very different. Abroad, the average age of an entrepreneur is around 36 and, usually, they are middle management individuals who break out of the corporate job to start their own business. Here it is totally different; they start very early at university and they are a lot younger.

And how do you see this affecting the overall economy?

Wasfy: I think the entrepreneurial scene will lead the economy one day. They are working under a lot of barriers and hindrances from the government, but they are working their way steadily and speedily. I think one day they will change the economic scene in Egypt. We have seen this; Fawry just sold for millions of dollars, so I am very optimistic.

Saeed: One of the difficulties in Egypt is that most small businesses and SMEs run in the informal economy. It’s a parallel economy. That’s why one of the services of accelerators is to legalise the companies as well. The District co-working space, for example, offers their address so that you can register the address there.

Which are the sectors that have particular strength, and which are the ones that need to be boosted?

Saeed: Everyone agrees that ICT is the dominating sector for startups for several reasons: it is the easiest and you can scale globally; there is a lot of talent – Egypt is actually doing very well in ICT – and it is requires small investments in the seed stage. I can invest $10,000 to develop an app and launch it, so there are a lot of mentors and investors involved. In terms of challenging sectors, anything related to hardware - when we talk about industrial startups, whether in agriculture or industry - is really facing a hard time because of the difficulty to obtain permits. I recently met an entrepreneur who recycles waste to build furniture, and has been waiting for two years to obtain a permit.

Wasfy: We need more focus on industrial and agricultural startups. Personally, I have not seen anybody working in the agricultural field. When I attended the Global Entrepreneurship Summit in Kenya, there was a huge amount of startups working with agricultural projects because it is very good fit for the country. But here, most startups and accelerators are tech-based; even angel investors are focusing on this field, so there is no diversification.

Saeed: In Aswan, Assuit, and Minya, these people are serving the local community so you find a lot more ideas on agriculture and industry fields. The problem is that it is very hard for them to grow their businesses in their community; they often need to come to Cairo, meet the ecosystem, and often face a language barrier because applications are in English.

"The revolution opened a door for people to start to think, innovate, create, and control their destinies," says Mahmoud Wasfy.

Globally, there seems to be a boom in startups working in the collaborative economy. How do you see the sector evolving in Egypt?

Wasfi: Until now, the shared economy didn’t show progress in Egypt. We have seen entrepreneurs working with carpooling, but it was not a massive success. There are some cultural barriers that explain this; for example, for people to share a ride. People are starting to notice and get engaged in this, but I have not personally seen particular success.

Saeed: I think it is happening. It is a global trend; and you can see it here in the co-working spaces like The District - entrepreneurs don’t come for free wi-fi or office space, they come seeking collaborations. It’s happening in carpooling applications like Uber and Careem; and RiseUp, a sharing initiative. Everyone is communing for collaborations and you have this massive amount of content in the end, which is not created by RiseUp - it is a collaborative effort. It is still not a competitive environment in Egypt, and there are ethics to be considered, because so far there are no two startups growing in the same industry. But when competition gets tougher, we will see if we are collaborating with each other and how ethics come to play.

Every entrepreneur seems to refer back to the revolution. Do you feel they have somehow taken the revolution’s demands in their own hands?

Saeed: We are not like Tunisia, which is an innovation-driven country. The government there is, in fact, supporting entrepreneurship; there are a lot of entrepreneurship centres developed by the state itself, linking them with banks with micro-financing options. The government is developing something for the region. They are on top of it in Africa, together with Kenya.

In Egypt, it is mainly taught in private universities, which additionally have developed entrepreneurship centres. In public universities, student activities are leading the scene as well as some professors who have exposure and private business, who bring entrepreneurs to lectures. However, there is no curriculum to teach it. It is not a governmental priority. We spoke to the Ministry of Investment and they are aware it is happening; they are monitoring it, but it is not their priority. The main priority for them is land allocations and permits for industrial startups, which will end up benefitting entrepreneurs as well.

Wasfi: The revolution opened a door for people to start to think, innovate, create, and control their destinies. But in terms of legalisation and government involvement, we have yet to see it. However, the mindset of people has changed.

To get the book, follow Startology on Facebook.

- Previous Article Breaking News: Hurghada Hotel Attacked By Armed Assailants

- Next Article CSquare's Al Mafrood Webseries Tackles and Entertains