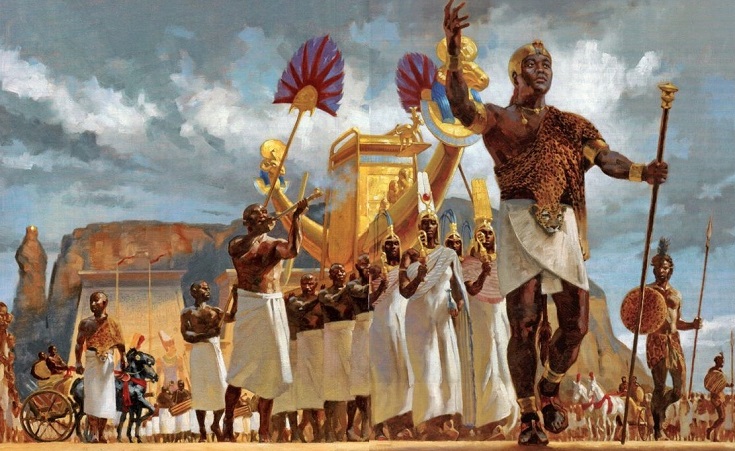

The Nubian Return Caravan: Family Feud or A Darfur Scenario?

As demands for Nubian repatriation rise, we revisit the history of the Nubian plight, which was eclipsed by separatism conspiracy theories, racism, and the rise of Arab nationalism.

We all know the story; a knight comes riding on his noble steed, conquers, and plants his banner in the hearts of his king’s new subjects. It’s the timeless tale of love, loss, and diaspora, passed down from one generation to the next; it’s a bedtime story, a meal that tastes of what used to be, a lingering smell of home long after it’s gone, and a never-ending song.

Nubian rights activists Ramy Yehia and Fatma Emam Sakory grew up in Cairo; with the fading smells of their aromatic Nubian heritage, they never spoke their ancestors’ tongue nor felt the soil of Old Nubia between their fingers. “I can’t speak my own language. It hurts. I listen to my people’s songs and I don’t understand what is being sung,” Yehia says pensively. There was no mention of them in school books, “My uncle would give me novels like El Shamadoura (The Buoy) by Mohamed Khaleel Qassem, I’d read the works of Hassan Nour, Yehia Mokhtar, Mohy El Deen Saleh – it became my alternative history,” Sakory reminisces.

The plight of Egyptian Nubians dates as far back as 1899. Once a region spanning from present-day northern Sudan to Southern Egypt, Nubia was divided between the two countries by an Anglo-Egyptian Condominium agreement that annexed the north to Aswan and placed Sudan under joint Egyptian-British control. The partition tore up families and marked the beginning of the Nubian diaspora.

1902 was the onset of the Nubian exodus, when the British built the Aswan Low Dam to store floodwater and expand the production of cotton. The reservoir was built across the Nile River, a few kilometres south of Aswan. The reservoir was heightened twice, leaving more than 25 Nubian villages flooded.

The great disaster, however, was the erection of the High Dam and the construction of its adjoining reservoir, the Nasser Lake. The lake fully inundated the fortress of Buhen and other Ancient Egyptian sites, as well as the Nubian Valley, and its residents were to be resettled in Kom Ombo, 50 kilometres north of Aswan. According to Yehia, the process didn’t quite go as planned. Some claim the authorities didn’t account for Nubians who were displaced in the wake of the Aswan Reservoir’s construction in 1902 and its subsequent elevations, and, by some accounts, the housing projects were built in the desert, which resulted in the deaths of a large number of elderly people and infants during the first year of resettlement. Naturally, many fled to the north.

According to Yehia, the process didn’t quite go as planned. Some claim the authorities didn’t account for Nubians who were displaced in the wake of the Aswan Reservoir’s construction in 1902 and its subsequent elevations, and, by some accounts, the housing projects were built in the desert, which resulted in the deaths of a large number of elderly people and infants during the first year of resettlement. Naturally, many fled to the north.

But the Nubian ordeal didn’t end there. As Arab nationalism became more prominent in North Africa and Western Asia, with the decline of the Ottoman Empire, ethnic and religious minorities in these regions saw their cultures marginalised and effaced by the growing hegemonic socio-political ideology. Kurds and Yazidis in Syria and Iraq, ethnically African minorities in Sudan, and Amazighs and Sahrawis in the Maghreb all began to face systematic racism, as did Nubians in Egypt. “The state has had this problem since Nasser; this is someone who changed Egypt’s name to the United Arab Republic, and even after [the Egyptian-Syrian union] crashed and burned, Sadat added the designation ‘Arab’ to the country’s name in the 1971 constitution,” Yehia declaims. “North Africa is still very much culturally occupied by Arabs, and some use the language argument to convince you that you’re ethnically Arab. Senegalese people speak French, does that make them French? Does it make the country French?”

Aside from the occasional photo op, the exclusion of Nubians from Egyptian policymaking has always been the norm, but many saw renewed hope for inclusive reform and actively pursued it following the popular uprisings of 2011 and 2013, only to lose sight of it soon after. “There has always been a pattern, and within the pattern there are nuances; Mubarak would put investors ahead of Nubian Egyptian citizen, and The Muslim Brotherhood [under Mohamed Morsi’s rule] were overtly hostile towards us – they resented anyone who was different from them,” Sakory says.

The Nubian rights movement’s demands didn’t crystallise until 2013, following months of campaigning by Yehia and Sakory, among others, who would later serve as aides to Nubian novelist Haggag Oddoul during his service on the constituent committee – known as the committee of the 50. “We helped draft and pass three or four articles stipulating the cultural, social, and economic rights of Nubian Egyptians and that was, no doubt, a quantum leap for us,” she asserts.

Their political victory was short-lived. Their claim to the lands they were to be repatriated to - as per article 236 of the constitution, which grants Egyptian Nubians the right to return to their historical lands - were undermined by two presidential decrees. In 2014, President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi issued decree no. 444, which annexed 16 Nubian villages to a military zone, barring civilians from it; in August 2016, he announced directive no. 355, by which 922 acres of said lands were allocated for the Toshka development programme. Additionally, in October 2016, in what seems like a concerted effort to thwart Nubian repatriation, the government launched the 1.5 Million Acres project, which put 110,000 acres of historically Nubian lands in Toshka and Forqandy up for sale by public tender. “The narrative is this: ‘we’re trying to sell you lands to cultivate and develop and Nubians won’t let us’ – but the truth is, 80 percent is tendered to investors,” Yehia says.

This time, though, Nubian organisations wouldn’t budge for the greater good as they always have, and threatened to file a complaint to the African Commission on Peoples’ Rights to abrogate decrees 444/2014 and 355/2016. And on November 5, 2016, the Nubian Return Caravan set out to Toshka in protest of the allocation of Nubian lands for the 1.5 Million Acres project. But because anything that can go wrong has a tendency to go worse, security forces wouldn’t let the protesters through and a four-day sit-in ensued, blocking the Aswan-Abu Simbel road, during which they were reportedly sieged and famished. “The government responded by giving Nubian Egyptians priority over other groups when buying our own lands back,” Yehia snarled.

This time, though, Nubian organisations wouldn’t budge for the greater good as they always have, and threatened to file a complaint to the African Commission on Peoples’ Rights to abrogate decrees 444/2014 and 355/2016. And on November 5, 2016, the Nubian Return Caravan set out to Toshka in protest of the allocation of Nubian lands for the 1.5 Million Acres project. But because anything that can go wrong has a tendency to go worse, security forces wouldn’t let the protesters through and a four-day sit-in ensued, blocking the Aswan-Abu Simbel road, during which they were reportedly sieged and famished. “The government responded by giving Nubian Egyptians priority over other groups when buying our own lands back,” Yehia snarled.

On November 23, the protesters suspended their sit-in pending a meeting with the prime minister that was set to take place yesterday – November 28th. In the meantime, shuttle negotiations with the cabinet and the presidency, mediated by members of parliament, were on-going.

Although the constitution grants Nubian Egyptians full citizenship rights, recognises their right to return to their historical lands, and upholds their cultural, economic, and social rights, the gross injustices that have befallen them and the sacrifices they have made for their country are eclipsed by a scare-mongering prevalent cultural narrative of conspiracy theories and unwarranted distrust. “Egyptians all love each other, but once you start demanding your rights, you’re a collaborator and a traitor,” Yehia remarks. “The cause is completely unacknowledged – there’s no mention of it in the media, or even our school curriculums, so people’s perception of it is coloured by misconceptions because the information is not available, and our version is not factual to them, but rather contested and subjective.”

This social chasm is rooted in the abject racism dating back to the monarchy and propagated by Egyptian pop culture – the caricatural 'Othman the steward who speaks broken Arabic' stereotype that has become our very own blackface, making assimilation near to impossible for Nubians. “Nubians remain closed to society because they haven’t quite been integrated, because it’s racist, because they’re patronised and marginalised, because they're treated appallingly – so, yeah, it makes sense for them to be isolated,” Yehia says authoritatively.

As the nation awaits resolution, there are those who wrap themselves in the flag and stoke separatism with divisive rhetoric, knowing full well that Egyptian Nubians are not completely without recourse, but would rather keep it in the family. “We’re not after the internationalising the cause, and, by the way, there’s nothing unpatriotic about it. It’d be treason if this was a reclusive country like North Korea, but Egypt is part of the international community; besides, we wouldn't demand citizenship rights if we were separatists, would we?” Yehia says. “Egypt is a signatory of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as the International Covenant on Social Economic and Cultural Rights, and has ratified them, and both uphold the rights of ethnic minorities,” Sakory explains.

The Pan-Arabist tributary regimes in Iraq and Sudan committed atrocities against ethnic minorities, which culminated in the Kurdish genocide in the 80s and the on-going annihilation of Darfur’s non-Arab population, not because Arab Nationalism demands blood, but because racism is a slippery slope. “People should be very afraid of a Darfur scenario in Egypt if the deadlock between Egyptian Nubians and the state continues. This is not something we want, but at the end of the day, those who have armaments are the ones who start wars,” Yehia states. “We’re pushed into a corner with our backs against the wall, our arms are being twisted, but we have rights and we are demanding them. They can’t possibly convince us otherwise, that we have no right to return to our lands.”

(Main image illustration: National Geographic)

(Photos of the Nubian Return Caravan: Hisham Abd El Hamed)