Boikutt: Hip Hop and the Soundscape within Palestine’s Walls

Ahead of his performance in Cairo at D-CAF, Palestinian musician Boikutt Muqata'a talks inspiration, commodification, and what it means for an independent artist to stay genuine.

Politically unfiltered, artistically pounding and stylistically explorative, Boikutt Muqata'a stands against the trials of commercial genres to embody a genuine expression of a nascent Hip Hop scene pushing its way through the Arab world through social media and live shows. In a movement that some would call the “return of the aura to local music”, the Palestinian artist trades clichés for blunt manifestos against the commodification of art, sometimes leaving the “dirt” in the sound. “Because that’s what reflects the political soundscape we live in,” he says.

“Advice from one brother to another: stay independent / Because the games are being played, so steer clear of the trap / Let them wait for foreign aid until they die,” his song Letter from Boikutt reads.

Having led the band Ramallah Underground together with Asifeh and his brother Aswat, Boikutt performed all over the world, including shows in Austria, Australia, the UK, Egypt, Holland, the US, and a collaboration with the Kronos Quartet. After launching his solo career, he released his first album Hayawan Nateq in 2013.

“I started playing the piano when I was seven, and then came the guitar and the Oud; but it became serious when I was 12, when I started trying things out and discovering making music,” he says. The trajectory of his Palestinian refugee parents through Lebanon, Syria, Tunisia, Algeria and Cyprus left a mark on the young musician, who was born in the USA but raised between Cyprus and Palestine.

You have a very intercultural background. What made the biggest impact on your music?

I am not sure whether it made an impact on my music, but I’m pretty sure it impacted the way I think and see things. I never feel like there is a place that I can call home, because I moved so much. I feel like I’m an alien wherever I go.

Even in Palestine, where the Diaspora’s cultural identity is so strong?

As a Palestinian, you are always searching for a new identity, because we have so many different identities, and at the same time just one; it’s very complicated. You can be from Jerusalem, from the West Bank, you can be a refugee from 1948, or a refugee who is not living in a camp. All of these share one same identity, but there is also a lot of division between them. To me, my identity comes first as a human being. I’m not a nationalist person, I don’t see it as a matter of borders; I see our struggle more as a struggle for decolonisation than for the creation of a nation-state.

How has the occupation affected your career?

It’s hard to pinpoint because I’ve lived under occupation most of my life. We have small communities with a tiny art scene, like Ramallah, Bethlehem, Nablus, or Haifa. But the occupation made it really difficult to have a music scene or a proper art scene, even though Palestine is such a small place. We are divided, so that really affects our work. I try to collaborate with a lot of people and part of my work is basically travelling, performing and doing shows, and that is very difficult in Palestine; I’ve only done two cities so far in Palestine; it’s easier for me to perform anywhere else in the world than in my homeland.

How do you feel your music can contribute to resistance?

I don’t give my music to Palestinians, I give it to everyone who wants to listen to it, regardless of where they are from. To me, the most important thing that might come out of my music is to start a discussion,to spark up a conversation. It’s not about just me saying my opinion, because I see it as a two-sided communication. That’s why it is important not to say what people want to hear, and also not to preach to the crowd.

I try to put the audience in an uncomfortable spot when listening to the words and the music, so I use a lot of noisy sounds. A lot of people try to make the sound cleaner; I just leave all the dirt in it and make it even dirtier, because I think expresses the environment where I live in.

One of the biggest statements for me is to be independent, because I see, particularly in the art sector, that a lot of people are dependent on culture centers or financing, and they are not really creating art with these thousand dollar commissions. I understand that everyone needs to live; I have nothing against that and I live off my music as well, but it’s about being completely independent, because that is the only way you create art. When art is created only after the artist is paid, it loses its true expression. I am not saying that everyone who gets paid is creating commodified art. The problem is when artists don't create anything unless they are paid to do it. You can’t sit and force things to come out. Some of my best work comes out just spontaneously, while I am doing something else.

And what’s the time of the day when you feel most inspired?

Usually in the evening, because it’s when I feel my work is done. I always wake up early and try to get everything done. That’s why I don’t go out that much at night anymore.

What inspires you?

A lot of Jazz and Trip Hop, which really changed the way I see music. Bands like Portisaid and Massive Attack; when I heard them it was a turning point because I thought ‘I can take this music and develop it into something good’. Other than that, I listen to Glitch music, Ambient, Psychedelic Rock, Minimal Techno, Punk, Drum and Base, a lot of stuff. I don’t actually care for genres; I just make what I think sounds good.

Who is your best critic? Who do you go to when you want to try something?

My brother. He is a sound installation artist, and we are together part of a group called Tashweesh, together with visual artist Ruanne Abou-Rahme. It’s electronic audiovisual, experimental, noisy, ambient. My brother has always been very harsh with criticism to me, and I think that criticism is what made me what I am today.

What would you say is the biggest myth about Hip Hop?

There are many misconceptions, but the problem is that most of them are true as well. One of the biggest ones is that Hip Hop mainly talks about money, cars, and women. And unfortunately, there is a lot of commercial, commodified Hip Hop coming not only from the USA, but even from Germany, or Arab countries.

Where do you feel the Arab Hip Hop scene is going?

There are a lot of new people coming out now; and I think that Arabic Hip Hop is really still in its early stages and only now starts to show different styles, that are not even geographic anymore. It was geographical two years ago, but it’s become very mixed and it’s not about the sound of each city, as much as more about people with their own styles and schools being developed.

Random question: If you had to choose another historical moment to be born in, what would you choose?

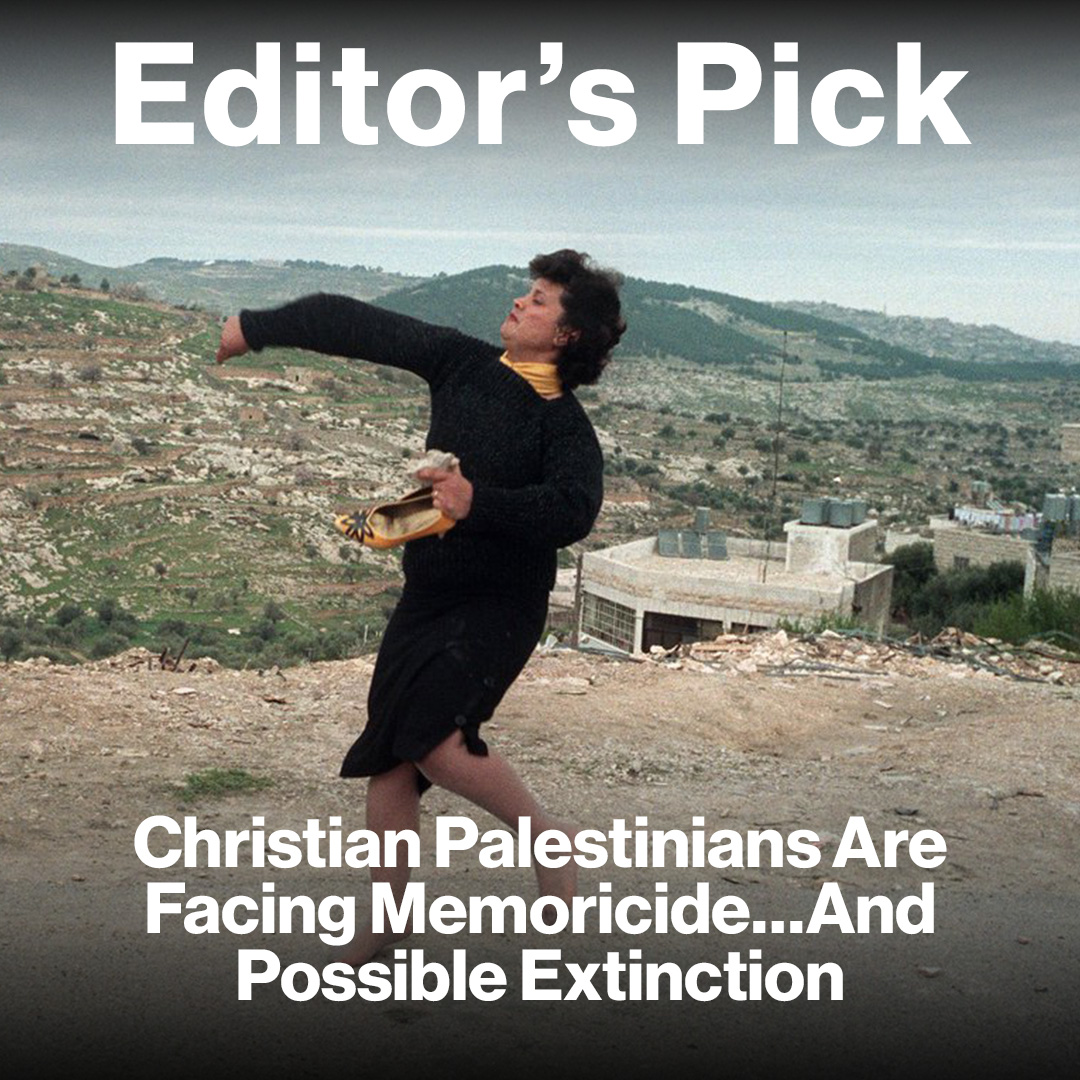

To be honest, every single time in the history of Palestine sounds like it wasn’t better than today. It is obviously getting worse, but it just seems like Palestine has always been occupied and colonised, ever since I can remember. Maybe I’d like to go back to the Canaanite times, or at least before 1948, when we had people of all colours and religious beliefs; there was no division between people even if we had the British mandate at the time.

I still don’t see Palestine today divided religiously, but the Zionist state wants a pure Jewish state, and that’s why we are divided religiously. From the stories I hear from my grandparents, there were people of all beliefs living together, and that to me sounds like something great. I’m not talking about Zionist Israelis, I’m talking about Palestinian Jews who were living naturally in that place. I’m not talking about peace between Palestine and Israel, I’m talking about decolonising.

Do you believe in the two-state solution?

I’m totally against the two states. I think the only way is one state; one state of anything. But of course achieving that means the end of Zionism.

You have released your album, played for the cinema and the theater; you are living your aspirations. Are you enjoying it?

Definitely. But success is a very relative term; to me, it means being able to make music whenever I want. Of course I always look for more, but what I dream is learning to play more instruments, and learning more about the physics of sound mixing and mastering. Making music is always an ongoing process, I develop my musical skills every day and it’s very important to keep doing that. It’s an ongoing research.

- Previous Article This Is A (Wo) Man's World: Chef Julia El Bardai

- Next Article Train For Aim Heads to Palm Hills